Comorbid conditions continue to be a concerning and complicating factor in relation to the medical management of injured workers, with comorbidities being identified as the number one barrier to recovery among a recent survey of 500 industry stakeholders.1 The survey also placed comorbidities as the number two concerning claim complexity, beating out factors such as injury type and undetected fraud, waste and abuse.

Obesity is a known comorbid factor that negatively impacts recovery from injury and is associated with increased workers’ comp costs among non-minor injuries.2 According to NCCI, workers’ comp claims with a comorbid diagnosis have twice the medical costs of similar claims.3

Obesity is a complex disease that occurs when an individual has a body mass index (BMI) – a rough estimate of body fat percentage – of 30 or higher.4 An estimated 42% of Americans are considered obese,5 putting them at risk for several serious diseases and health conditions.

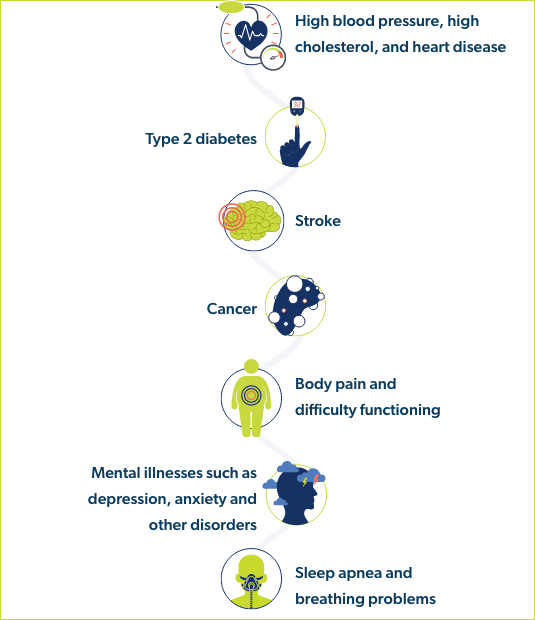

People who are obese are at increased risk of:6

The wide-ranging health impacts of obesity also lead to significant healthcare spending and employee costs.

is spent annually on obesity-related medical care in U.S. adults7

to be lost time claims3

According to the CDC, factors that can cause or contribute to obesity may include diet and physical activity patterns, sleep routines, genetics, certain medications, and social determinants of health.8

Considering that the causes of obesity can vary, it may be beneficial to employ a multifaceted approach when treating obesity, one that includes diet, exercise, lifestyle changes, and in some cases, prescription medications.

In the last few years, there have been several new drugs approved for the treatment of obesity, along with an increase in the off-label prescribing of certain diabetes medications for the treatment of obesity. Some of these drugs have even gained serious media attention

For instance, the drug Ozempic® (semaglutide) received endorsements from public figures such as Oprah and Elon Musk, and the TikTok hashtag for Ozempic received over 273 million views; many have attributed this attention to have caused drug shortages for Ozempic.10

Meanwhile, Wegovy® (semaglutide) has seen such successful sales that the manufacturer is struggling to keep up with demand, currently working to double the quantity of lower doses reaching the U.S. by investing $11 billion to expand global production capacity.11

Not only are there shortages of these new drugs, but the demand for them is so high that the FDA published warnings about counterfeit semaglutide products that are available in the U.S. supply chain.12 In another notification, the FDA alerted consumers that compounded semaglutide products marketed for weight loss contained the salt formulation of semaglutide instead of the base formulation, meaning it was a different active ingredient and not proven to be safe or effective.13

While many in the industry find it unlikely that workers’ comp could see a significant amount of these drugs end up in claims, some have argued that there may be precedent, albeit limited, where workers’ comp payers were required to reimburse weight loss programs and bariatric surgery in special cases.14

Currently, the industry is beginning to experience some level of creep, with some of these therapies beginning to trend in workers’ comp prescription drug transaction data compared with 2023.15 And while the overall number of scripts is still very small, the high cost associated with a single prescription can quickly have an impact on spend, making it a drug category to watch.

Additionally, if more group health plans cover these medications, it is worth being informed of the impacts these drugs can have on overall patient health.

Regardless, there is much to learn with these new medications, especially as more are currently in development.

While there are many prescription drugs available for the treatment of obesity, this new wave of medications has been based on certain type 2 diabetes medications that – when combined with diet and exercise – demonstrated significant weight loss.

This led manufacturers to develop new formulations of these diabetes drugs, specifically tailored for the treatment of obesity. Ongoing research is still underway to offer more oral formulations instead of currently available injections.

However, approval and availability are two different things. Due to shortages in FDA-approved therapies specifically indicated for obesity, prescribers in some cases are continuing to prescribe certain diabetes medications off-label for weight loss.

These new diabetes/obesity medications fall into two categories: GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors.

Originally developed to help manage type 2 diabetes by controlling blood sugar levels, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists send signals to the brain to create more insulin. This lowers blood sugar and delays digestion and appetite, making individuals feel full for longer.16

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found that GLP-1 agonists can help to attain 8-21% weight loss when combined with diet and exercise.17

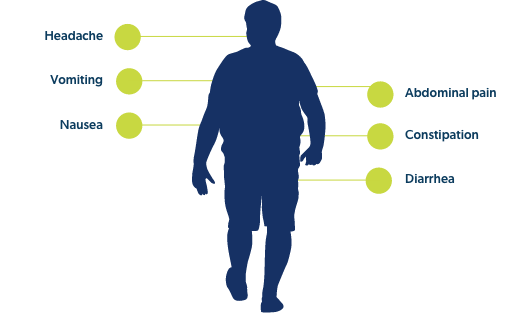

While each individual drug within this class offers unique warnings and precautions, several of them come with warnings for thyroid C cell cancers, pancreatitis, and hypoglycemia in conjunction with insulin. Additionally, the following adverse reactions were common across this drug class:

Wegovy® weekly injections – approved for the treatment of obesity

Ozempic® weekly injections – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but prescribed off-label for the treatment of obesity

Rybelsus® tablets – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but prescribed off-label for the treatment of obesity

Zepbound™ weekly injections – approved for the treatment of obesity

Mounjaro® weekly injections – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but prescribed off-label for the treatment of obesity

Saxenda® daily injections – approved for the treatment of obesity

Victoza® daily injections – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes

Trulicity® weekly injection – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but prescribed off-label for the treatment of obesity

Byetta® twice daily injections – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but prescribed off-label for the treatment of obesity

Byudreon BCise® weekly injections – approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but prescribed off-label for the treatment of obesity

Retatrutide injectable – Phase 3 trials have begun

Orforglipron tablets – Phase 2 trials were recently completed. Of note, it is believed that if approved, this drug will be easier and more affordable to produce18

The FDA has been evaluating reports of suicidal thoughts or actions in patients treated with GLP-1 agonists, but their preliminary evaluation has not found evidence that these medications cause suicidal thoughts or actions.

The information provided to the FDA was often limited because those events could have been influenced by other factors, and therefore a clear relationship was not demonstrated.

However, because of the small number of suicidal thoughts or actions observed in both people using GLP-1 RAs and in the comparative control groups, the FDA cannot definitively rule out that a small risk may exist; therefore, the FDA is continuing to look into this issue.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors were originally developed to help treat type 2 diabetes. SGLT-2 inhibitors lower blood sugar by promoting glucose excretion in the kidneys, removing glucose from the blood via urine, leaving less glucose in the body to turn into fat.20

However, as SGLT-2 inhibitors help burn more calories from the body, this could cause an increased appetite. Monotherapies with SGLT-2 inhibitors are not very effective for weight loss, which is why they are only recommended for weight loss when prescribed with agents that reduce food intake.20

While current clinical research found that GLP-1 agonists are more effective for weight loss than SGLT-2 inhibitors,21 SGLT-2 inhibitors may still be considered popular obesity medications due to ongoing drug shortages, the fact that these medications are available in oral formulations instead of injectables, and due to differences in patient profiles that could make GLP-1 agonists less appropriate for certain individuals.

However, it is important to note that all SGLT-2 inhibitors at this time are only FDA-approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in combination with diet and exercise. Any use for the treatment of obesity is considered off-label prescribing.

Invokana® (canagliflozin) tablets

Steglatro® (ertugliflozin) tablets

Farxiga® (dapagliflozin) tablets

Jardiance® (empagliflozin) tablets

Brenzavvy™ (bexagliflozin) tablets

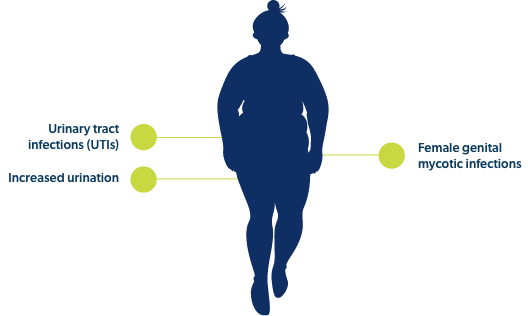

Though each individual drug within this class has its own set of precautions and contraindications, commonly noted adverse events across SGLT-2 inhibitors include:

While newer obesity medications may be gaining popularity, it is important to keep track of pre-existing medications, which may see continued use. These drugs may be used by themselves or in combination with newer obesity drugs. And even if newer obesity drugs continue to see prolonged popularity, these pre-existing drugs could still be offered as alternatives in the event of drug shortages or if patient-specific factors rule out the use of GLP-1 agonists or SGLT-2 inhibitors.

As there is a growing diversity of obesity medications available, the clinical considerations across these drugs also grow more diverse.

Considering the high number of individuals affected by obesity and the rapid-growing popularity of these therapies, it is likely that a portion of workers’ comp patients may be prescribed these drugs outside the scope of their workplace injury – making it helpful to understand how these drugs can impact overall patient and pharmacy management.

As this area of drug development continues to evolve, here are additional considerations as they relate to patient safety.

As newer obesity drugs continue to dominate headlines, non-obese individuals may attempt to obtain these drugs. However, these drugs should only be used in obese populations.

Misusing or overusing anti-obesity medications could lead to overdose, low blood sugar, and an increased risk of harmful side effects.

These medications are meant to assist in the loss of weight, not directly cause weight loss. They must be effectively combined with diet and exercise. Failing to do so will reduce efficacy.

Obesity drugs are meant to be taken long-term, and if an individual stops taking them, they risk regaining weight. In one study from Diabetes, Obesity, & Metabolism, individuals on these medications lost an average of 17.3% of body weight, but upon quitting the drugs they regained 11.6% of body weight, averaging a net loss of 5.6% overall.22

Many semaglutide products on the market are injectable pens with clear directions on how to set the dial for the correct dose. However, patients may be overzealous and injecting themselves with more semaglutide than recommended.

Poison control centers saw a 1,500% increase in calls related to semaglutide injectable products in 2023, approximately 3,000 calls.23 Many patients have overdosed on semaglutide, resulting in seizures, confusion, passing out, fatigue, weakness, nausea, vomiting, chills, dizziness, and other symptoms.

The sheer popularity of these new anti-obesity drugs has led to drug shortages. If an individual were to receive these obesity medications and had to stop due to ongoing drug shortages, it is important to understand the clinical ramifications – when patients have on-and-off access to these medications, they may experience strong weight fluctuations, which can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.24

The high demand for anti-obesity medications has led to many opportunistic individuals trying to cash in on this trend. This, of course, creates questions surrounding the efficacy and safety of medications that a patient may be receiving, raising red flags for pharmacotherapy.

The FDA warned consumers regarding the presence of counterfeit semaglutide products in the drug supply chain, making it important for workers’ comp stakeholders to keep an eye out for fake products that could endanger patients.12

Additionally, the FDA alerted consumers that compounded semaglutide products marketed for weight loss contained the salt formulation of semaglutide instead of the base formulation, meaning it was a different active ingredient and not proven to be safe or effective.13

Finally, individuals may receive anti-obesity medications from medical spas, medical clinics, and weight loss clinics23 – understanding whether or not these products are legitimate, counterfeit, or compounded may be difficult to ascertain.

The pharmacy landscape for anti-obesity drugs continues to evolve, as more new medications are still in research and development. More medications could see approval in the next few years, and it is possible that certain GLP-1 agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors currently approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes could gain approval as anti-obesity medications, whether or not they are available in their current dose or a higher dose.

Additionally, currently available anti-obesity drugs could see label changes in the next few years, with additional indications or precautions as clinical research continues.