One irresponsible prescriber can ruin countless lives, as evidenced by the 2015 murder conviction of a California doctor whose copious opioid prescriptions led to overdose fatalities in multiple patients.1 More recently, a New York doctor was convicted of selling opioid prescriptions—signing blank prescriptions for his receptionist to fill out with medications such as hydrocodone and clonazepam—a practice that demonstrated high disregard for the health and safety of his patients.2

Thankfully, these extreme offenders are few and far between. But they also only represent a portion of inappropriate opioid prescribing. What about the well-intentioned prescriber who makes misguided prescribing decisions? Whether uninformed or underinformed on the latest treatment guidelines, there is a vast opportunity to communicate with these prescribers to influence their prescribing in a way that benefits the patient’s care.

Thus, while claims management strategies often emphasize the need to analyze patient data to impact the course and outcome of a claim, it is equally important to understand and address prescribers’ behaviors, because they influence the care of all their patients—creating opportunity for broader-impact interventions.

The specialty of prescriber from whom a patient receives their opioid prescription can vary depending on factors that include the timeframe in which the opioid is prescribed following injury, injury type and severity, and whether surgery or other medical intervention has occurred. Therefore being able to identify intervention opportunities means putting prescribing trends in the correct context.

For example, a significant portion of first-time opioid fills occurs in the emergency setting, but trends show us that many of these patients don’t go on to continue opioid therapy past the initial fill – and if they do, it is another prescriber specialty who is making the decision to continue their therapy. 3

Thus it is more important to look at long-term prescribing habits. Who is prescribing opioids for longer durations of therapy? Why might they be doing so? And importantly, where are there potential areas for concern and intervention?

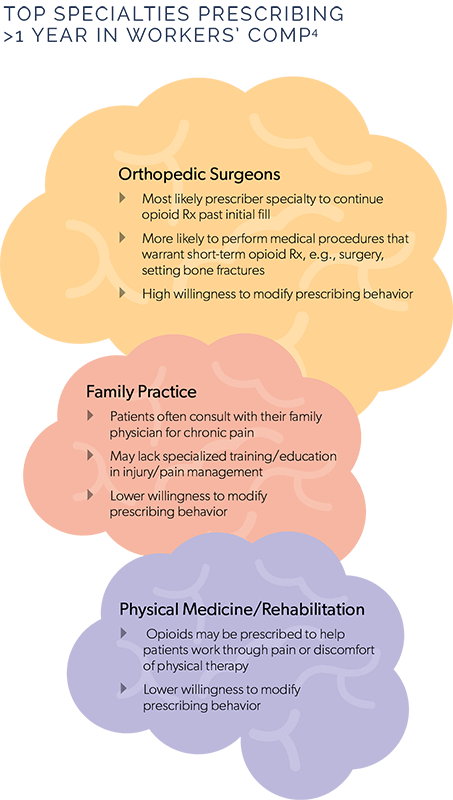

While national statistics tell us that family practice physicians prescribe nearly half the prescription pain medications dispensed in the U.S.,4 in workers’ compensation, orthopedic surgeons are the prescriber specialty most likely to continue opioid therapy past the initial fill.3 This decision point has a tremendous impact, as a patient’s odds of remaining on opioid therapy long-term (>6 months) significantly increases with their second fill.5

It isn’t surprising that orthopedic surgeons would prescribe opioids, as evidence-based guidelines recommend them for acute postoperative pain. What is surprising is how often orthopedists prescribe opioids beyond the post-op phase and over the long-term. A surgical procedure such as knee arthroscopy would be expected to allow full activity at approximately 6 weeks, while the average shoulder surgery puts the patient in a sling for 4-6 weeks. Typical timeframes such as these bring into question the medical need for duration of opioid therapy to continue for months or even years.

The good news? Statistics show that orthopedic specialists often have a high willingness to modify their prescribing behaviors.3 This presents a significant opportunity for communication with these prescribers.

Patients often seek treatment for chronic pain through their primary care (family) doctor. Thus family physicians prescribe a high volume of opioids despite a potential lack of formal training in chronic pain management. These physicians are often not equipped with complete knowledge of the risks associated with these medications, which can present significant patient management concerns.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued last year their Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, which is intended to educate primary care physicians to the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy and provide guidance on proper initiation, management, and discontinuation of these medications.

While the guideline provides a strong framework for guidance, direct communication with a family physician may bring to light clinical guidance that they can apply not only to the individual patient at hand, but to future prescribing habits.

While opioid prescribing rates have decreased overall in recent years, they have remained higher among certain prescriber specialties, including physical medicine specialists.4,6

Opioid medications may be beneficial in this setting, serving to manage pain as patients work through the discomfort of physical therapy with a goal to improve function and facilitate recovery. If the patient continues to show functional improvement, opioids may continue to be appropriate even into the sub-acute or chronic phase of treatment. However, continued monitoring is important to determine whether the benefits of long-term opioid therapy continue to outweigh the significant patient safety risks. And it is critical that opioid use be tapered and discontinued as early as possible.