Fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA) is an unfortunate fact of life for workers’ compensation payers who must contend with a variety of issues that drive up costs, compromise care for injured workers, and undermine the workers’ compensation system.

Workers’ compensation insurance fraud costs are estimated to be $34 billion per year, with $25 billion attributed to employer fraud and $9 billion attributed to worker fraud.1 Employer fraud usually involves efforts to lower premiums, often by misclassifying or under-reporting employees. Worker fraud is when an employee misrepresents the facts of an injury in some way, such as exaggerating symptoms to prolong paid time off, making a claim for an injury that occurred outside of work, or faking an illness or injury altogether.

The third, and possibly most expensive, type of fraud that impacts workers’ compensation payers is healthcare/provider fraud.

Workers’ comp payers must provide all necessary medical care for injured workers, which makes them highly susceptible to healthcare system fraud, which is estimated to total $100 - $300 billion per year across public and private payers.2 And fraud is just one part of the FWA triangle that drives up healthcare and workers’ compensation costs across the country.

Of the $4.5 trillion in annual U.S. healthcare spending,3 approximately 25 percent is considered wasteful,4 and three to 10 percent is estimated to be fraudulent.3 It’s a huge problem that affects all healthcare payers and administrators, including those in workers’ compensation.

Fraud, waste, and abuse are often lumped together, but they are three distinct issues, although closely related and with some overlap.

Fraud is generally considered a crime and abuse can be a crime depending on circumstances, such as frequency and level of abuse, as well as intent.

Healthcare provider fraud and abuse come in many forms and can range from a small number of incidents by a single entity to widespread endeavors by groups or organizations. Medicare and Medicaid are prime targets for large-scale fraud, but private healthcare payers – both group health and workers’ comp — also experience regular fraud and abuse.

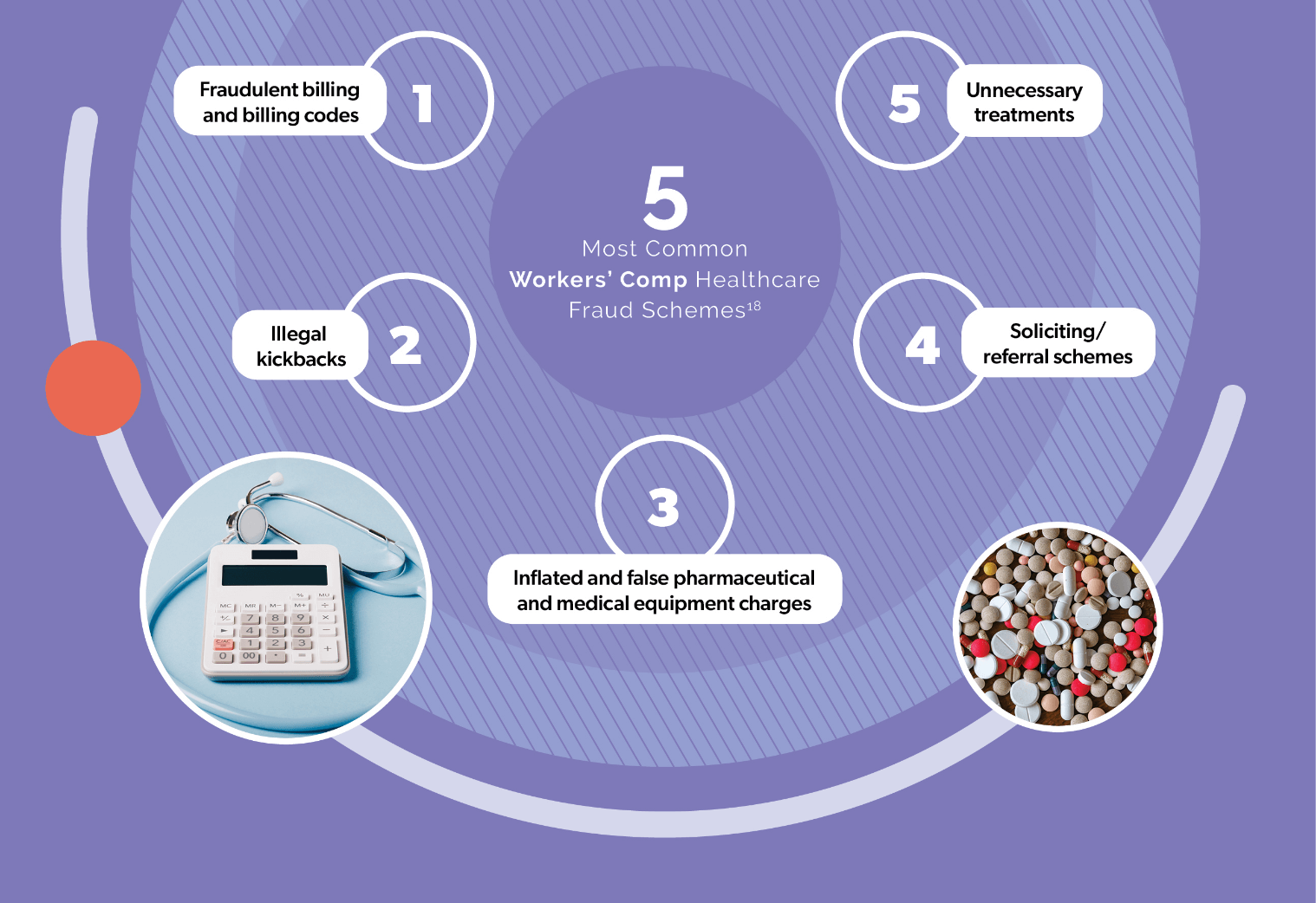

The sheer size and complexity of the American healthcare system creates a lot of opportunities for unethical, negligent, greedy, and careless behaviors. Common types of FWA that occur in both group health and workers’ comp include the following.

Generally speaking, all forms of healthcare FWA are relevant to workers’ compensation care. As a group, injured workers receive a wide variety of medical services and claims must be filed with and approved by insurers for payment. However, there are some nuances to combatting FWA in workers’ comp.

Because workers’ compensation benefits and the regulations that guide them are determined by state lawmakers, the benefits afforded to injured workers are often more generous, as compared to group health, and insurers sometimes have less leeway in limiting costs and services. In addition, the state-by-state system creates 50+ separate departments/bureaus of workers’ compensation, and hundreds of insurers and TPAs who authorize and pay claims from thousands of healthcare service providers. This makes it harder to detect suspicious activity because bad actors can distribute schemes across a wide network of stakeholders.

Workers’ compensation is a fraudster’s paradise!6

Other factors, such as the size and composition of a state’s workforce, the type of injuries that are compensable, and the state’s medical oversight regulations and resources, may make some states more vulnerable to fraud and abuse. For example, a $200 million fraud scheme in California was perpetrated there because of three combined factors: generous benefits; a large population of migrant workers who had limited English language skills and even less knowledge of workers’ comp; a large and cumbersome system with limited oversight capabilities. 7

Another example of how the idiosyncrasies of states’ workers’ comp systems can result in more fraud, waste, and abuse is a Florida statute that has entitled injured workers to “free full and absolute choice in the selection of the pharmacy or pharmacist dispensing and filling prescriptions for medications required,” which has led to physicians dispensing/selling medications directly to patients or through third-party mail order services, both of which result in unnecessarily high pharmacy costs and potential harm to patients.8

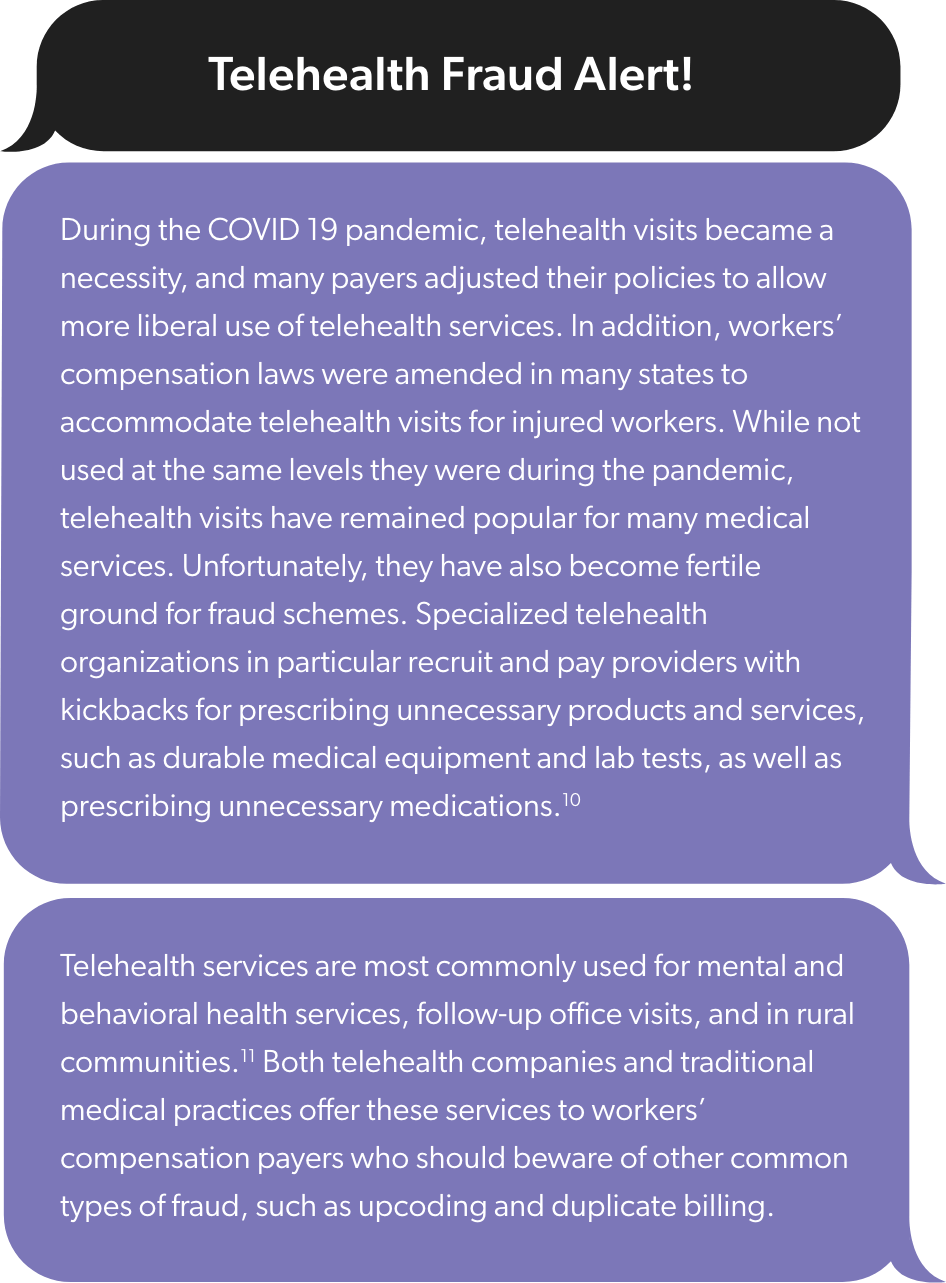

Expanding compensability for mental health conditions might also lead to new cases of FWA, given that about 20 percent of healthcare fraud is attributed to mental health services9 and it has become increasingly common for these services to be provided via telehealth.

While each state has its own variables, they also share commonalities that create widespread opportunities for fraud, waste and abuse. Most notably, workplace injuries frequently involve the treatment of pain, which led to excessive rates of opioid abuse over the last two decades. At the height of the crisis 55% of injured workers were prescribed opioids12 and approximately 30% of those were still filling prescriptions after 90 days.13 Worse still, opioid abuse was found to account for 61% of drug-related deaths among workers with lost-time injuries.14 Fortunately, opioid prescriptions have decreased dramatically in workers’ comp. But abuse and addiction risk with opioids remains high and there are other concerning drugs and prescribing practices that warrant vigilance in workers’ comp medical management.

The types of injuries common in workers’ comp also often require a large variety of medical services, including diagnostics, physical therapy, durable medical equipment, and more. Ancillary services such as these can be challenging to manage and are ripe for several types of FWA, including upcoding, overutilization, kickback schemes, and more. One case in California involved $310,000 of fraudulently billed translation services. 15 Much larger dollar amounts were involved in a physical therapy fraud scheme in Texas where $80 million of inflated and fraudulent physical therapy and durable medical equipment were charged to the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Workers’ Compensation.16

Workers' compensation fraud, waste and abuse costs billions of dollars every year and causes financial stress for individual payers and the system as a whole. It also hurts injured workers. Some of the lost money could potentially have been used to provide more or better benefits. Worst of all, medical fraud, waste, and abuse can compromise care and directly harm injured worker patients.

For example, the previously cited $200 million fraud case in California involved hundreds of workers who were subjected to unnecessary and sometimes painful treatments, including unneeded medical devices inserted into their spines.7 More broadly, a study sponsored by Johns Hopkins School of Bloomberg Public Health found that patients seen by medical providers who were later banned due to FWA were 11 to 30 percent more likely to require emergency hospitalization and were 14 to 17 percent more likely to die than patients treated by providers in good standing.17

Patients seen by medical providers who were later banned due to FWA were 14-17 % more likely to die than patients treated by providers in good standing.

In addition to compromising care and risking injured worker health and recovery, incidents of FWA have a damaging effect on the injured worker experience and can undermine confidence in the workers’ compensation system and its ability to provide quality care.

The methods of committing FWA in healthcare are myriad. The number and diversity of potential perpetrators is even larger. One line of defense that is often effective against FWA is expert knowledge and experience. Claims staff and clinical case managers often spot an anomaly – or a suspicious pattern – that indicates inappropriate or suspicious activity. Over time, different types of FWA become known and healthcare payers and benefits managers employ a variety of methods to combat them. But the large scale and constantly evolving variations of FWA incidents in healthcare can only consistently be detected through data.

A standard FWA identification method used today is rule-based detection. Rule-based detection involves developing rules to mine claims data and identify known FWA behaviors, such as upcoding, duplicate bills, inappropriate utilization and more.19 Rules can be written to identify patterns of FWA at various levels, such as provider, patient, or transaction. Rules-based FWA detection is commonly used and has been successful. Indeed, many insurance carriers, TPAs, PBMs, and other industry stakeholders are currently reducing costs and improving health outcomes using rule-based data detection. But this method may become insufficient as fraud schemes and waste/abuse patterns change.

The global healthcare fraud detection technology market was valued at $1.1 billion in 2021 and is estimated to reach $3.6 billion by 2031.20 This projected growth is mainly due to advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and its ability to learn and adapt as conditions change.

Even uncomplicated rules-based detection systems involve thousands of algorithms that must be rewritten to accommodate changes as simple as updating NCCI codes.21 In contrast, some AI models, including machine learning and natural language processing, can update themselves through continuous learning and adaptation to observed changes. AI can enable the automation of applied analytics to swiftly identify signs of both known and potentially new types of FWA. AI’s ability to accurately detect signs of FWA at higher volumes and in a fraction of the time could lead to significant cost savings and better health outcomes for injured workers.

However, adopting these models is not without risk and complications.

AI-driven models vary, but many share the ability to detect patterns and anomalies over vast datasets and hundreds of thousands of variables that humans are not equipped to analyze. To do this effectively, AI models rely on a store of relevant and clean data. Claims data, which generally contains all of the medical transaction records, is the most essential and commonly used data set for FWA detection.19 However, claims data contains personal health information (PHI), which is protected by federal privacy regulations and cannot be legally shared without patient consent. This can make it difficult for healthcare organizations to use some commercially available generative AI models, such as ChatGPT, due to security risks.

Two ways around this problem are for organizations that store PHI data to use large language learning models that do not expose it and/or to utilize generative AI models internally and train them to access relevant new information while keeping PHI secure. Using these advanced technologies to keep up with evolving fraud schemes requires a high degree of technical expertise, which will take time and money to build across the industry. More time may also be needed for stakeholders to have confidence in AI models and to develop the necessary multi-disciplined cooperation needed to build successful applications.

As promising as AI appears to be as a tool to reduce FWA in workers’ comp healthcare, it is not likely to be the sole tool. Workers’ comp organizations can already employ a multi-pronged approach to effectively combat FWA using a combination of evolving data-driven tools combined with human expertise.

A combination of technologies and human oversight will always be needed to effectively combat FWA now and in the future, including:

Healthesystems’ proprietary ancillary benefits management program was created to address unmanaged FWA in medical products and services commonly used for injured worker care.

Delivering medical care to help injured workers recover and return to work is a critical component of the workers’ compensation mission and accounts for approximately half of its total costs.22

Awareness of evolving FWA and how to effectively detect and prevent it are crucial to containing costs and ensuring the best possible care injured workers.