There are many lasting effects of the COVID-19 virus to both individuals as well as the healthcare industry. Although the incidence of COVID-19 was on the downturn, there has been an uptick due mainly to a new variant in the unvaccinated population. The best way to prevent future medical and financial implications of the virus is to ensure that all workers for whom the vaccine is medically indicated are consulting with their healthcare providers to get vaccinated. This is one of the ways to prevent ongoing long-term effects of the virus and keep our workforce safe and healthy.”

Robin Martin, RN, BSN

Ancillary Services Manager, Johns Eastern Company, Inc

Though many individuals who are infected by COVID-19 recover completely within a few weeks, there are two groups of individuals who face longer-term health impacts from the virus.

Long-haul COVID-19 cases involve individuals who recover from a milder case of the virus but still experience COVID-19 symptoms for months after the fact, or potentially even longer.

Severe COVID-19 cases involve individuals who were so debilitated by the virus that they required hospitalization, which may have included long-term intubation or respirator assistance. In these cases, infection was so strong that the patients’ bodies were left significantly impacted, in some cases leaving them with permanent health conditions.

In both cases, it is important to note that COVID-19 is still being studied. For a virus that has only been researched for under two years, the clinical understanding of long-term effects is still limited. New research studies are still being launched, and new data and information may continue to change our understanding of just how COVID-19 impacts the body.

When an individual recovers from a milder case of COVID‑19, they may still experience COVID‑19 symptoms for weeks or months after being infected by the virus. This can happen to anyone, no matter how mild the case. Even people who had COVID-19 and were asymptomatic could experience post-COVID-19 symptoms.1

The persistence of long-haul symptoms is more prevalent in older individuals, or people with serious medical conditions, but these symptoms can still appear in young and healthy people, causing them to feel unwell for weeks to months.2 And because COVID‑19 research is still in its infancy, it is possible symptoms could last even longer.

One study of 1,700 patients discharged from a Wuhan hospital found that six months after infection, 63% of patients still suffered from fatigue and muscle weakness.3 A Swedish study found that eight months after mild infection, 11% of people had at least one moderate-to-severe symptom that had a negative impact on their work, social, or home life.4

Long-term COVID-19 symptoms vary greatly on a case-to-case basis, especially as they impact individuals with other health concerns or comorbidities.

Anecdotal reports show that vaccination among those previously infected by COVID-19 can reduce or eliminate long-haul symptoms.5 While more research is necessary to establish the scientific validity of these reports, this could create hope for those suffering from long-term COVID-19 symptoms.

When an individual contracts a severe case of COVID-19, they may require hospitalization, intubation, or even respirator assistance to stay alive.

These severe cases can be incredibly traumatic for the body, and despite the best efforts of healthcare professionals – who should be applauded for their work throughout the pandemic – these patients could go on to experience a wide range of long-term or permanent impairments.

As this article explores a limited range of these impairments, it is important to note that recovery for these impairments varies. According to the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM), disability will be better defined with more research over time, but recovery duration for these bodily impairments may be correlated with case severity.6

In hospitalized patients, general skeletal muscle deconditioning is expected in patients who are intubated for any extended duration. These patients may require exercise programs and possibly rehabilitation services to recondition their bodies and prepare them for an active lifestyle once more. Furthermore, if these patients are cleared to return to work after a severe case of COVID-19, they may require lighter physical duties as their bodies continue to recover.6

Medical research has yet to determine just how long patients may experience skeletal muscular deconditioning after a COVID-19 hospital stay. Many of these complex cases will need to be addressed by occupational and environmental medicine physicians.

What is known is that some hospitalized and severely affected individuals will incur long-term disability with permanent impairments of the cardiac, respiratory, neurological, and/or musculoskeletal systems. There is also the potential for a minority of patients to be permanently totally impaired.6

COVID-19 can directly attack the organs, creating many different types of health problems if the organs sustain too much damage. The biggest known targets are the lungs, heart, and brain.

In severe cases of COVID-19, the lungs can be so irreversibly damaged that lung transplantation is the only option for survival.9

In addition to COVID-19 potentially attacking the brain directly, long-term hospital stays and the need for intubation and ventilation can be a traumatic experience, and it is possible that many patients may develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from the experience.2

Among patients who develop ARDS, 30-55% of individuals experience cognitive impairments, while 40-60% experience psychiatric abnormalities.6 While it is too soon to fully explain why this is, damage to the lungs could provide the brain less oxygen, keeping it from working as efficiently as it did prior to infection.

Dozens of states across the nation have passed legislation requiring workers’ comp coverage for COVID-19 cases that can reasonably be shown to have been developed in the workplace. Certain federal occupations could also be subject to similar rulings.

Workers’ comp payers may be required to pay for COVID-19-related treatment, including long-term health impacts caused by the virus, making it important for payers to understand these clinical concerns.

Though it will be some time before the scientific community fully understands the long-term health impacts of COVID-19, we are seeing clear evidence that the virus can lead to chronic health concerns.

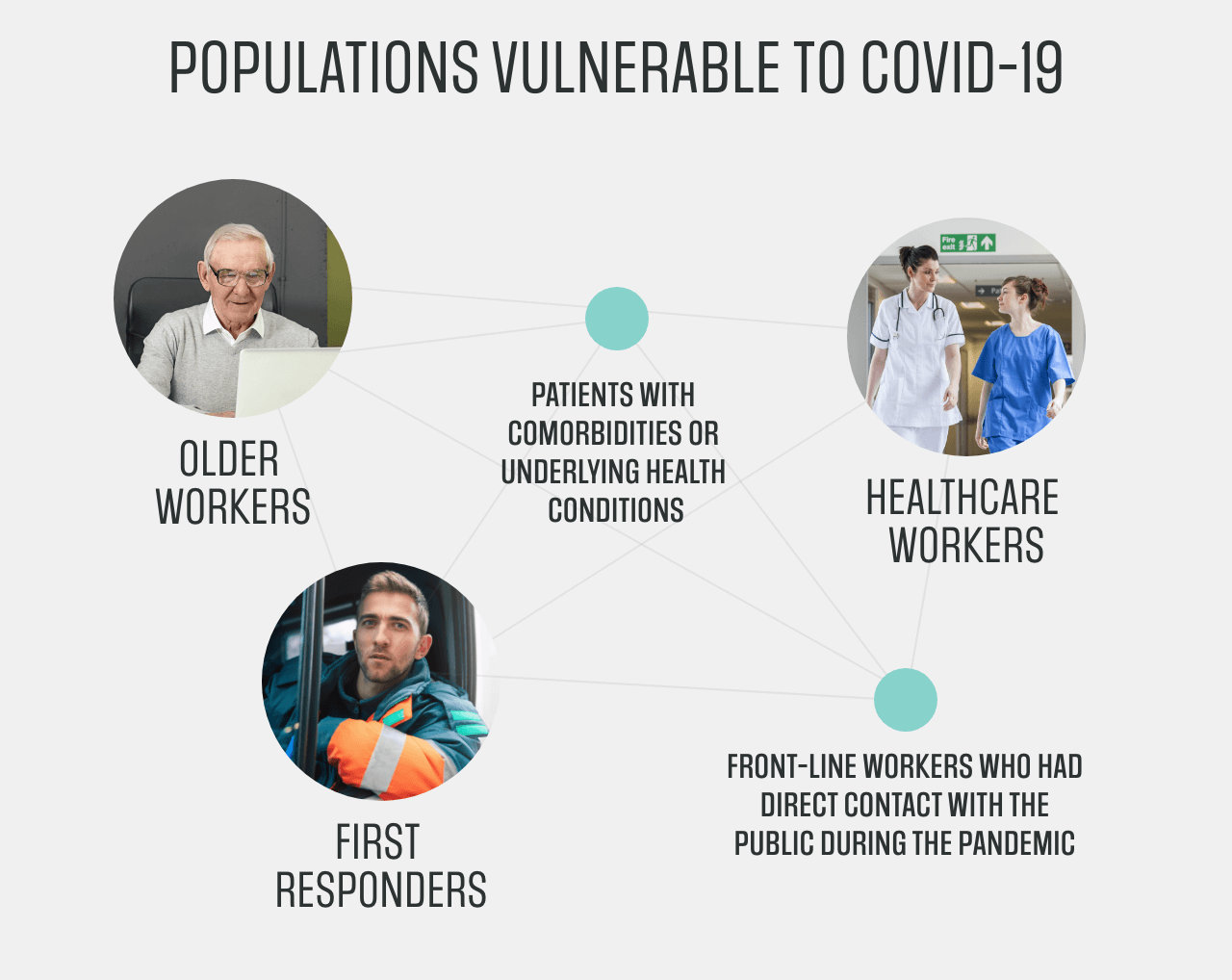

The long-term health problems caused by COVID-19 could be considered a comorbidity when they compound other unrelated health problems or injuries. As in any at-risk population, these long-term concerns will likely be a factor when managing the care of workers’ comp populations, as the prominence of this virus could leave an untold number of injured workers vulnerable.

If an injured worker is experiencing long-term COVID-19 health problems, then drug therapy should be approached with caution. Many drugs commonly prescribed in workers’ comp claims could be contraindicated against the health problems caused by long-term COVID-19. Furthermore, a patient may already be taking medications for long-term COVID-19, and those drugs could negatively interact with drugs the patient is taking for their workplace injury.

Your PBM partner can be leveraged to create formulary management strategies that incorporate these evolving population management concerns, while also providing engagement programs with individual prescribers and patients to address unique medication concerns.

When recovering from COVID-19, the symptoms or bodily damage experienced by the individual will vary greatly. Recovery duration from COVID-19 is correlated with case severity,6 and the adjustment of workplace duties may be required depending on an injured worker’s job description and severity of symptoms.

In mild cases, an employee may get tired more quickly, and this may only require a few extra rests during their workday. In more serious cases, a patient who spent extended time in the hospital may have experienced general skeletal muscle deconditioning and require lighter physical duties as their body recovers.

In even more severe cases, individuals may incur long-term disability with permanent impairments of the cardiac, respiratory, neurological, and/or musculoskeletal systems, which could fully impair their ability to fulfill the duties of their position or prevent return to work.

As we continue to learn more about the long-term impacts of this disease, it will be helpful to approach each individual case with compassion and an open discussion, understanding that what works for one employee may not work for another, and that several different solutions must be embraced to meet the unique needs of individuals.