The word “gig” began as slang used by musicians to describe one-time live musical performances and has since been adapted to refer to single projects or tasks for which a worker is hired.

While many debate what constitutes gig work, the gig economy can be characterized as an environment of short-term jobs or temporary contracts, which can include freelancers, independent contractors, temp workers, contract workers, on-demand workers, and other nontraditional work arrangements.

Gig work can vary from a few minutes to over a year, and can include traditional labor such as construction, manufacturing, IT jobs, retail, office work, and transportation.

In the face of economic upheaval and continuing technological innovation, the U.S. job market has undergone significant changes over the last decade, which has led to the rise of the gig economy.

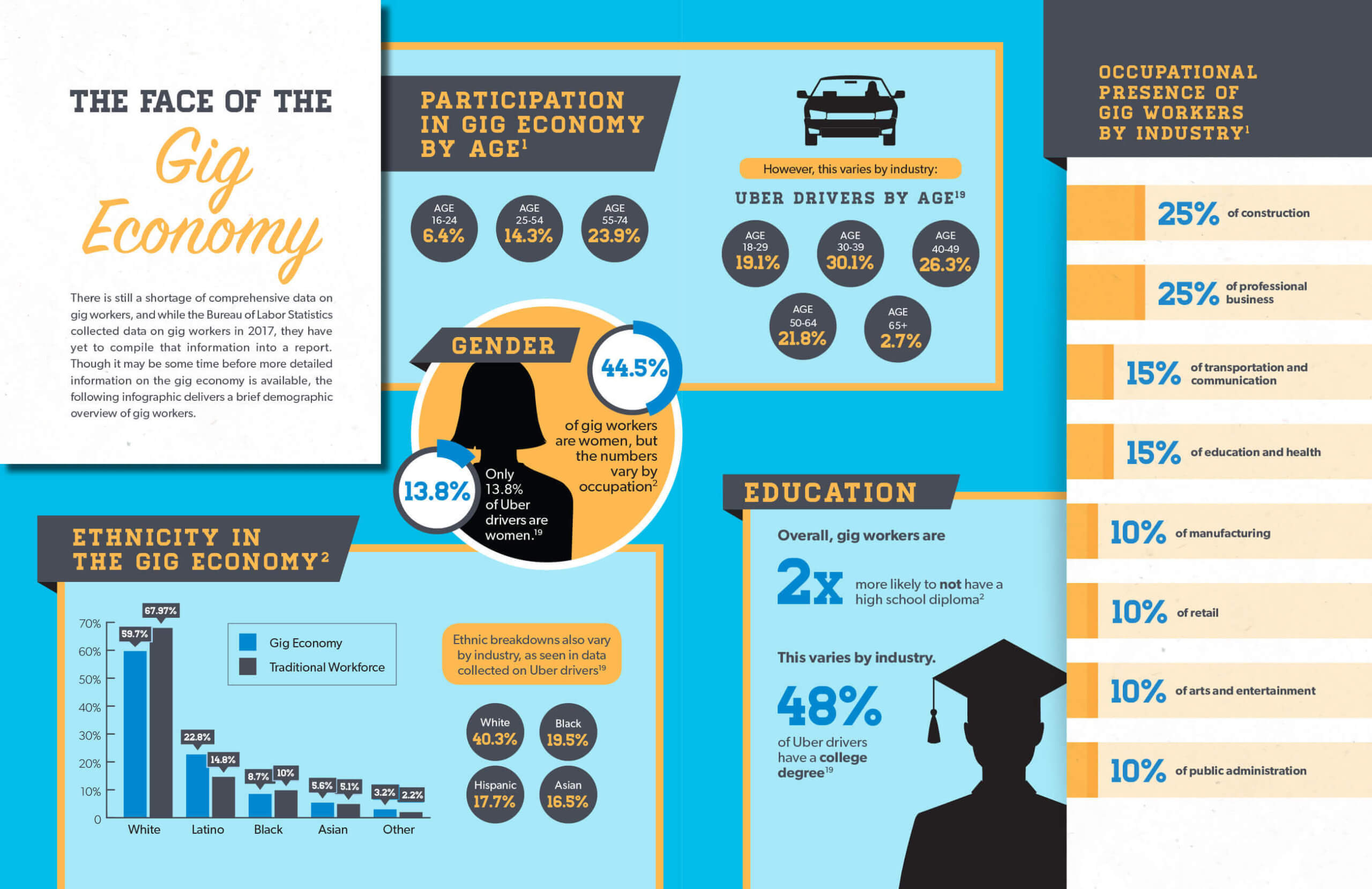

The National Bureau of Economic Research estimates that 23.6 million Americans, or 15.8% of the population, are part of the gig economy,1 while the Government Accountability Office calculates that, depending on the definition of gig work, as many as 40% of Americans could be considered part of the gig economy.2

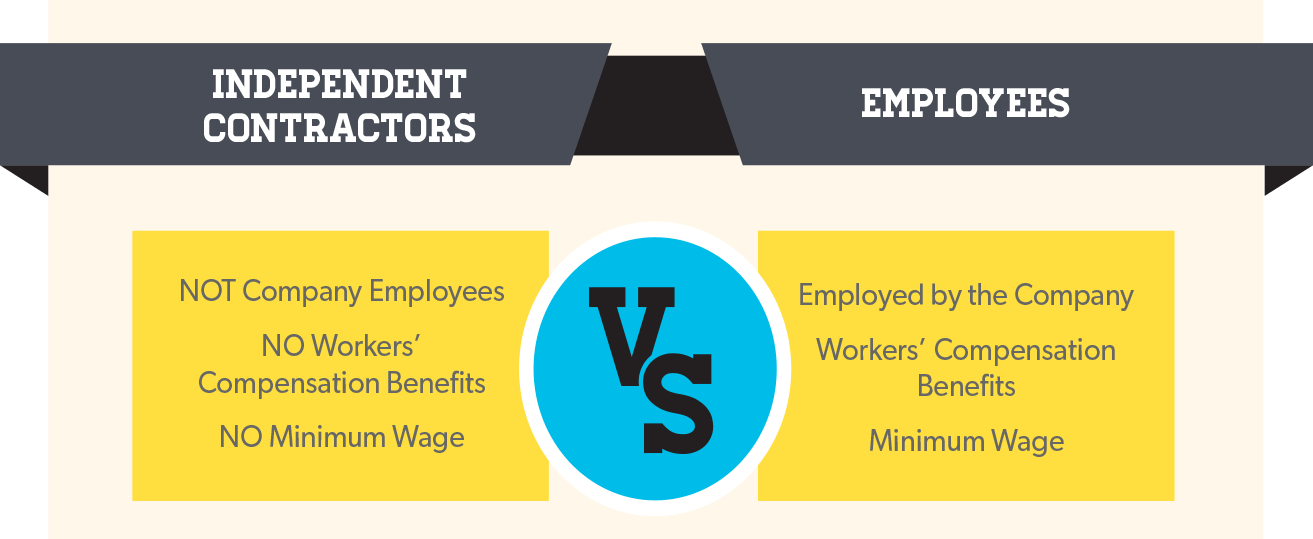

Regardless of definition, a common point of contention is that gig work often does not provide workers with employee benefits, including workers’ compensation. This has led to much debate as legislators have argued for and against the rights of gig workers, and as the gig economy is projected to grow further, this discussion could potentially impact workers’ comp.

The types of job functions within the gig economy are expected to increase as more industries reorganize their structures. The National Academies Press found that advances in technology and the interconnectivity of the internet have made it attractive for firms to reorganize their activities so that a greater share of work is performed by individuals who are not employees, but part of a project-specific workforce.3

Furthermore, most gig jobs serve to supplement the income for individuals who already have a traditional, primary source of income, and so even if the traditional job market were to grow stronger, the gig economy would not necessarily shrink in response. A study by McKinsey & Company estimates that 27-34 million Americans in the gig economy, or roughly 50% of gig workers, are supplemental earners.4 And while it may seem that a significant portion of gig workers could receive benefits through their primary occupation, a workplace injury in a gig job would not fall under the purview of these benefits, leaving a coverage gap.

Some organizations calculate that 43% of Americans will be part of the gig economy by 2020,5 while others believe that number will be 50% within a decade.6 Continued growth would mean the benefits concerns surrounding the gig economy will remain a prevailing conversation.

Across the nation, gig workers are widely identified as independent contractors instead of employees, meaning that they may not be entitled to certain rights, including workers’ comp, depending on the state or jurisdiction. However, there is a growing divide on the question of compensation, as some locales are pushing to grant gig workers certain employee rights.

Just as physical injury claims that rely heavily on pharmacological modalities to address the symptoms of pain without active therapies to promote functional recovery should raise flags, mental–only claims that fail to incorporate a psychotherapy component should raise concerns that the patient’s PTSD is not being adequately or effectively treated.

Furthermore, states such as Tennessee, Georgia, Kentucky, Utah, Florida, Iowa, and Colorado have introduced bills that aim to permanently identify gig workers as independent contractors in order to clarify that such workers are not entitled to employee benefits such as workers’ compensation.8

In April 2018, in the case of Dynamex Operations West Inc. v Superior Court of Los Angeles County, the California Supreme Court redefined what constitutes an independent worker, establishing three very specific criteria which a majority of gig jobs do not fulfill, essentially classifying those workers as employees who could be entitled to benefits such as workers’ compensation.9

In the case of Re the Estate of Carlos Esterley Cerrato Rivera v. West Bend Mutual Insurance Company, the Wisconsin Third District Court of Appeals found that temporary workers who are injured on the job do have the right to claim workers’ compensation benefits or sue their employer if they are injured on the job.10 At a policy level, Washington state introduced a bill that hopes to provide workers in the gig economy access to workers’ compensation and other benefits,11 while the City of Seattle gave taxi and ride-sharing drivers the ability to unionize and negotiate their benefits with employers.12

If the gig economy continues to grow, this policy debate could escalate, resulting in significant change. Currently, one major compromise that has gained much traction in this debate is portable benefits.

Portable benefits are benefits that have been paid into or are accrued into an employer-sponsored plan that can be transferred to a different employer’s plan or to an individual who is leaving the workforce, effectively following employees and allowing various employers to pay partial premiums. This can apply to benefits for health plans, retirement plans, workers’ compensation plans, and most other defined-contribution plans.

Portable benefits currently exist in several forms, as construction workers have long had access to multiemployer pension plans, and truckers’ unions long ago won similar benefits. However, as most gig workers are classified as independent contractors, they do not often have the federal right to unionize, and so gig workers have faced difficulties lobbying for such rights.

In 2017, New York City, home to 1.3 million freelance workers, created a portable benefits taskforce to study creative options to help contract workers gain access to benefits.13 Officials are hopeful that such programs can be modeled after the Black Car Fund, a program that adds a surcharge to all cab rides in the city to fund health insurance, workers’ compensation, and other benefits for cab drivers.14

The Black Car Fund is a program that adds a surcharge to all cab rides in the city to fund health insurance, workers’ compensation, and other benefits for cab drivers.14

California introduced a portable benefits bill in February 2018,15 and a Congressional bill introduced in 2017 pushed for portable benefits for gig workers, though no action has since been taken with this bill.16

And while there has been little legislative momentum for portable benefits, support for portable benefits is strong, as the CEOs for several major gig firms such as Etsy, Lyft, eBay, and Uber signed open letters voicing their support for portable benefits programs, hoping to gain the attention of legislators, business leaders, and other decision makers.17-18

If portable benefits become the path of least resistance for this growing concern, it is still unknown how such programs would function on such a large scale. Unanswered questions include who would manage care, how benefits would be brokered, how spending could be best managed in a multifaceted worker-employer relationship, and what practices would be best for different industries, especially for workers with multiple employers.

At the moment, there is very little beyond speculation to consider, but if the gig economy continues to grow as projected, that may change in the near future.