Lack of sleep is an epidemic in America, especially for working adults. More than 43 percent of U.S. workers are sleep deprived, with those most at risk working the night shift, long shifts, or irregular shifts.1 Occupational fatigue, or the inability to perform normal work tasks due to the constant feeling of tiredness, has far-reaching consequences for workers and workers’ compensation.

Adults need an average of seven to nine hours of sleep each night. However, 30 percent report averaging less than six hours. 1 This may be due to personal sleep habits as well as sleep disorders such as sleep apnea or insomnia. In fact, one in three American adults describe their sleep as only “fair” or “poor.” 2 Insufficient sleep leads to sleep debt (when you sleep fewer hours than your body needs), which can quickly lead to fatigue, which can result in slow reaction time, reduced attention, and impaired judgment.

In turn, fatigue in the workplace can lead to poor productivity at best, and injury or death at worst. Fatigue is estimated to cost employers more than $136 billion per year in health-related lost productivity3 – or $1,200 to $3,100 per employee annually. 1 And a 2023 survey of employers and employees in high-risk industries shows that fatigue remains the top safety risk across industries and the largest contributor to injuries in the workplace.4

As these injuries occur, workers’ compensation claims follow – as do increased injury costs and more time off the job for injured workers.

Workplace Fatigue: By the Numbers

Sleep disorders are conditions that affect sleep quality, timing, or duration and impact a person’s ability to properly function while they are awake. Common types of sleep disorders include:

Poor sleep hygiene and sleep disorders are two causes of fatigue, but there are many other factors at play, from type of occupation to workplace policies.

Shift workers are perhaps most at risk for fatigue. In the United States, approximately 15 million people work full time on evening, night, rotating, or other irregular shifts.6 Shift workers may find it difficult to get enough sleep during their time off. That’s because their internal clocks – or circadian rhythms – may not be able to adapt to an alternative sleep pattern. This leads to shortened and disrupted sleep and excessive sleepiness while awake.7

Shift-work occupations typically include law enforcement, transportation, healthcare, first responders, construction workers, service and hospitality workers, and military. According to one survey, people working in corporate management, transportation, warehousing, and manufacturing averaged the least amount of sleep.8 Another study shows that 92 percent of construction workers and 94 percent of transportation workers had two or more risk factors for fatigue. Such risk factors include demanding jobs, long commutes, and more.9

Source: National Safety Council 2017 Employee Survey on Workplace Fatigue9

In addition to shift work, long shifts and long weeks are also risk factors for fatigue. Studies show there is an increased risk of safety incidents and injuries when employees are working more than 12 hours daily or more than 55 hours weekly.10

Other risk factors involve workplace policies such as lack of or infrequency of rest breaks. Ten percent of workers do not get a rest break during their shift.5 Even a 10-minute rest break can help an employee recuperate from task-related fatigue or reduce the risk of work-related injuries. One study found that brief, regular breaks improved alertness and performance for overnight flight crews.11

Quick shift returns are yet another risk factor for fatigue. Fourteen percent of workers get less than 12 hours between shifts.5 Returns of less than 11 hours between shifts are associated with fatigue on the subsequent shift. In fact, shift workers see quick returns as more problematic than night work.12

Ninety-seven percent of workers have at least one workplace fatigue risk factor and more than 80 percent have two or more.5 The potential for injuries on the job increases when multiple risk factors are present. Risk factors for fatigue5 include:

Shift work

High-risk hours

Demanding jobs

Long shifts

Long weeks

Sleep loss

No rest breaks

Quick shift returns

Long commutes

Certain employee populations carry more risk factors for fatigue. The workplace populations13 most at risk for fatigue are:

Sleep is vitally important to health. Thirty-five percent of workers cite lack of sleep as a top impediment to a healthy lifestyle.14 And studies have shown6 that fatigue is linked to health problems such as:

In addition to affecting an employee’s well-being, these conditions also increase healthcare costs for employers.

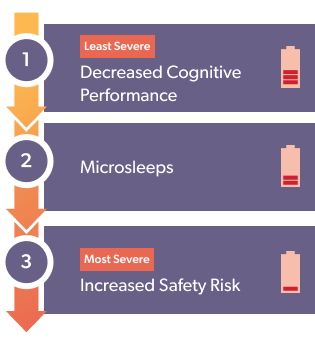

Beyond a worker’s health, fatigue has serious consequences within the workplace. One of the less severe consequences, and an early warning sign of fatigue, is decreased cognitive performance – a decrease in vigilance, attention, memory, and concentration, as well as slowed reaction time. Ninety-seven percent of workers reported experiencing these symptoms5 and 47 percent of employers experienced decreased productivity in their workforce due to fatigue.15

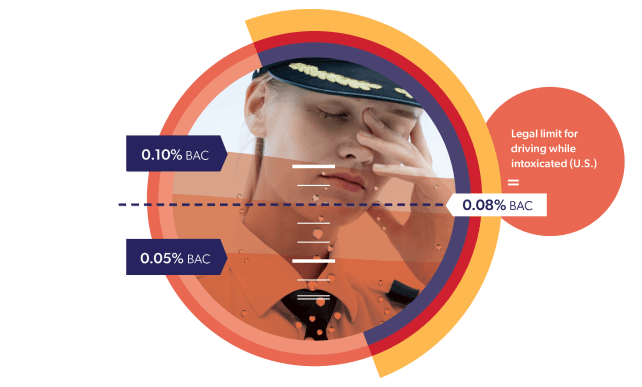

A second consequence of fatigue is microsleeps – or nodding off. Microsleeps are especially dangerous when employees are driving or performing a safety-critical task. Twenty-seven percent of workers reported experiencing microsleeps on the job, and 16 percent while on the road.5 The AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety estimates that 16 to 21 percent of fatal crashes likely involve drowsy driving.16 And car crashes are the leading cause of death for oil and gas extraction workers, who drive long distances to reach well sites in remote areas.17

The final and most severe consequence of fatigue is increased safety risk. Sixteen percent of workers reported at least one safety incident due to fatigue.5 And highly fatigued workers were 70 percent more likely to be involved in accidents than workers reporting low fatigue levels.18

Decreased alertness from fatigue isn’t just a threat to a worker’s personal safety; it’s a threat to those around them. For instance, workplace fatigue has contributed to industrial accidents such as the 2005 Texas City BP oil refinery explosion, which killed 15 workers and injured 180.19 What’s more, the National Transportation Safety Board has identified fatigue as a probable cause or contributing factor in 20 percent of their major accident investigations.20

And in the case of healthcare workers, patient safety is at stake. A report on 22 major occupation groups found healthcare support workers and practitioners had the second and third highest levels of short sleep duration and some of the highest prevalence rates of alternative shift work.21

Studies conducted with nurses show that working a 12-hour shift or working overtime is associated with nearly triple the risk of making an error, with the most significant risk occurring when nurses worked 12.5 hours or longer.22 And for physicians, very high sleep-related impairment is associated with 97 percent greater odds of making clinically significant medical errors.23

In the case of fatal patient outcomes, one study found that hospitals with higher patient mortality rates had higher rates of nurses working long hours, among other factors.24

For injured workers, fatigue can act as a barrier to recovery. According to a Workers’ Compensation Research Institute Study, mental health comorbidities including sleep dysfunction had a stronger association with smaller functional recoveries than physical health comorbidities.26

What’s more, in a study of stroke patients, fatigue was associated with poorer lower limb motor function, and with cognition indirectly via depressive symptoms.27 Another study shows that severe fatigue affects the recovery process and ability to return to work for heart transplant patients.28

While there are many over-the-counter sleep aids, prescription drugs are also an option to treat insomnia – though some are recommended only for short-term use. The examples listed below each come with their own safety and prescribing considerations; however, there are some factors to consider specifically related to injured worker populations due to how these agents may interact with other medications commonly prescribed within workers’ compensation.

Amitriptyline (Elavil®) and Trazodone (Desyrel®)

Clonazepam (Klonopin®) and Temazepam (Restoril®)

Eszopiclone (Lunesta®) and Zolpidem (Ambien®)

Ramelteon (Rozerem®)

Suvorexant (Belsomra®)

Sometimes drowsiness can be a side effect of an injured worker’s drug regimen. Prescription medications – many of which are commonly prescribed in workers’ compensation – that cause drowsiness or interfere with sleep include: