In 2021, an estimated 20.9% of U.S. adults (or 51.6 million people) experienced chronic pain lasting more than three months.1 And among people who have chronic pain, almost two-thirds suffer from it for more than a year.2

Workers’ compensation injuries almost always involve pain, with some workers suffering for the rest of their lives. In a 2020 Healthesystems survey of workers’ comp stakeholders, respondents ranked chronic pain as the most concerning health risk within claims populations.3

Chronic pain affects every aspect of a person’s life and even comes with health complications such as depression.4 In the workplace, the consequences of chronic pain include increased absenteeism, decreased productivity, higher healthcare costs, and higher levels of psychosocial stress.

When it comes to the treatment of pain, the workers’ comp industry has largely shifted away from opioid medications due to inappropriate long-term prescribing and the high potential for opioid abuse. But chronic pain isn’t going away – and it’s an inherent part of workers’ comp injuries. Let’s look at how chronic pain continues to affect workers, along with the latest non-opioid treatment options.

According to the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) practice guidelines, chronic pain is pain that lasts for at least three months.5 The Official Disability Guidelines (ODG) for the treatment of chronic pain also confirm this definition, while the Institute for Chronic Pain defines it as pain lasting more than six months.6 7

In the case of workers’ compensation injuries, pain occurs as a result of the injury and then persists beyond typical healing time. But it’s important to note that chronic pain may occur in addition to the pain of the original injury. Put simply, it is “pain that continues when it should not.”8

The most obvious cause of chronic pain is tissue damage sustained during an injury. The nervous system stays in a persistent state of reactivity even upon healing of the original acute injury or illness.9

But researchers have found that chronic pain can also be attributed in part to psychosocial factors. The most commonly assessed psychosocial factors in patients with persistent pain are depression, anxiety, and emotional distress as well as “negative affect” – negative emotions, thoughts, and behaviors.10

A frequent barrier to recovery among injured workers is “catastrophizing” – a cognitive distortion in which one exaggerates the negative consequences of their injury. Workers with high pain and high self-perceived disability are more likely to catastrophize their pain, leading to poor recovery outcomes.11

Chronic pain can affect anyone – but some occupations are more susceptible than others. Nearly half of healthcare workers are affected by low back pain, a common type of chronic pain. Hospital nurses are especially susceptible, likely due to the repetitive strain of lifting and transferring patients.12

A second group that experiences a higher proportion of chronic pain is construction workers. According to one study, about 40% of older construction workers over the age of 50 suffered from persistent back pain or problems.13

Yet another, perhaps more surprising occupation affected by chronic pain is high-speed boat operators. A systematic review shows that boat operators have a higher rate of injuries and a higher prevalence of chronic pain than the general workforce, with the pooled prevalence of chronic pain being 74%. The most common injuries were related to the lower back, followed by neck and head injuries.14

Another study found that a considerable proportion of workers in the petrochemical and petroleum refinery industries suffered from various types of chronic pain, with headache being the most frequently reported pain type (likely due to the polluted environment).15

No matter the occupation, the likelihood of experiencing chronic pain increases with age. An estimated 65% of U.S. adults over the age of 65 report suffering from pain and up to 30% of older adults report suffering from chronic pain.16 Other risk factors for chronic pain include genetics, previous injury, and obesity.17

Living with chronic pain comes with potentially serious complications, most notably an increased risk of depression and suicide. One study found that about 67% of people with chronic pain have a comorbid psychiatric disorder.18

More specifically, the prevalence of any anxiety disorder among people with chronic pain may be twice as high as in the general population, and panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are three times more common in individuals with chronic pain.19

Furthermore, in an evaluation of nearly 600 patients suffering from chronic pain, almost one third of patients with multi-site pain and neuropathic pain reported mild or major depressive symptoms.20

Suicide is the most serious and tragic complication of chronic pain, with risk of death by suicide at least double in chronic pain patients compared to the general population. Moreover, about 20% of those facing chronic pain experience suicidal ideation.21

Chronic pain affects every aspect of a person’s life, including their work life. The effects of chronic pain in the workplace include presenteeism, absenteeism, and higher healthcare costs. According to one systematic review, chronic pain has a substantial negative impact on work-related outcomes.22

Another review of return-to-work interventions for chronic pain notes that chronic pain remains the second most common reason for being off work.23 Indeed, one study concludes that people with pain missed three times as many days of work per year than non-pain respondents.24 And another study of workers disabled by a work-related injury concludes that those with severe pain symptoms were more likely to remain off work at 18 months post-injury versus those without pain symptoms.25

Another effect of chronic pain is presenteeism, when workers are at work but unable to fully perform their job duties. Interestingly, one study concluded that chronic pain was significantly associated with reduced performance at work (but not with missed work hours). The reported reduction in work productivity ranged from an average of 2.4 hours per week for adults with joint chronic pain to 9.8 hours per week for adults with multi-site chronic pain.26

In recent years, medical marijuana has increasingly emerged as a treatment for pain. As of February 2024, 38 states and the District of Columbia allow for the use of cannabis for medical purposes through comprehensive programs.27 Chronic pain is often considered a qualifying condition for medical marijuana. In fact, 38 state programs include a general category for severe or chronic pain or allow cannabis if opiates have been or could be prescribed for the condition.28

And while its use is far from typical, growing clinical evidence supports medical marijuana as a means for chronic pain management. There is also evidence that cannabis may play a role in helping to reduce opioid use, although that evidence is conflicting.

For example, a 2023 Journal of the American Medical Association study surveyed a representative sample of individuals aged 18 years or older with chronic pain who lived in states with active medical cannabis programs. Among adults who used marijuana in this study, more than half found that cannabis led them to decrease their use of prescription opioids, prescription non-opioid drugs, and over-the-counter pain medications.29

However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions that, while some research suggests that states legalizing cannabis for medical purposes experience a reduction in opioid prescribing and opioid-related deaths, other research has not indicated these associations – posing the question whether positive research findings could be coincidental.30

Note, too, that while medical marijuana has the potential to treat pain, there is still a need for more clinical research. Additionally, medical marijuana is not a first-line pain therapy and is generally used only when more traditional therapies fail.

Attending work with chronic pain is also associated with higher levels of psychosocial stress. According to one study, people with pain were:

The study concludes that the presence of pain in the workplace goes well beyond lost productivity due to absenteeism.31

Chronic pain is also associated with higher healthcare costs. In fact, it contributes to an estimated $560 billion to $635 billion each year in direct medical costs, lost productivity, and disability programs.32

Historically, opioid medications have frequently been prescribed to injured workers for acute pain relief. However, when used long term, they often lead to a cycle of misuse where patients develop a tolerance, dependence, and possibly even addiction. The opioid epidemic caused 400,000 overdose deaths between 1999 and 2017.33 And among the 47,055 drug overdose deaths in 2014, 61% involved an opioid.34

Due to the dangers of opioid abuse, the workers’ compensation industry has made a concerted – and largely successful – effort to curb inappropriate opioid prescribing and use. A Workers’ Compensation Research Institute study of 27 state workers’ comp systems found that prescription opioid utilization is decreasing while the use of alternative pain management therapies is on the rise.35

Opioid alternatives commonly prescribed to treat pain include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen; adjuvant analgesics such as antidepressants and anticonvulsants; and medications without pain-relieving properties such as those that treat insomnia, anxiety, depression, and muscle spasms.

Of note, in January 2025 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a novel, first-in-class, non-opioid analgesic indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. The drug works by targeting and interfering with the pain-signaling system, stopping pain signals from reaching the brain.36

The work to curb opioid utilization in workers’ comp is just one part of a larger national effort. Over the past decade, more than 3,000 state and local governments have sued opioid makers and distributors for their role in the opioid crisis.37 The sheer number of these suits – and their success – is proof of the national shift in attitudes on opioids and their shrinking role in pain management.

As of January 2025, the latest settlement involves Purdue Pharma and its owners (the Sackler family), the makers of OxyContin, who have agreed to pay a maximum of $6.5 billion. Most of the money will go to state and local governments for opioid addiction prevention and treatment programs.38

Chronic pain treatments range from conservative approaches like physical therapy to more invasive procedures such as surgery. No single approach works for everyone, and research shows that a combination of therapies is more effective than individual treatments.39

In recent years, workers’ compensation providers have switched from treatments involving pain medications and other restorative therapies to a treatment protocol that relies on non-pharmacologic services.40

According to the Workers’ Compensation Research Institute, these are the most frequent non-pharmacologic pain services billed under workers’ compensation:

Active physical medicine, or physical therapy, refers to exercises and movements performed by the worker. These include stretching, strength training, and stability training. Physical therapy is typically used in the later stages of treatment once an injury has begun to improve.

Passive treatments such as electrical stimulation therapy or hot and cold therapy are administered by the therapy provider to the affected area. These are used in the early stages of treatment when the injured worker cannot yet do active exercises.

This includes epidural procedures, facet and sacroiliac joint interventions, trigger point injections, and other injections and nerve blocks.

These include manual therapy and massage as well as chiropractic manipulations.

A key component of traditional Chinese medicine, this involves the insertion of very thin needles through the skin at strategic points on the body.

There are also many non-pharmacologic treatments for pain that simply don’t show up as frequently in workers’ compensation claims. These include:

These are intensive interdisciplinary programs occurring on a daily basis for three to four weeks. Program staff usually includes psychologists, physical therapists, physicians, nurses, and sometimes occupational therapists and vocational rehabilitation specialists. Program therapies include stretching and core strengthening, relaxation therapies, individual psychotherapy, non-narcotic medication management, and tapering of narcotic pain medications. On average, patients achieve a 40% reduction in pain by participating in a rehabilitation program.41

CBT for chronic pain, or CBT-CP, aims to alter the negative cognitions, emotions, physical sensations, and maladaptive coping behaviors that perpetuate the chronic pain cycle. A review of 35 studies revealed that CBT reduced pain intensity in 43% of trials.42

An investigational treatment for pain, VR is a computer-generated simulation that immerses users in a three-dimensional, interactive environment. In 2021, the FDA authorized the first VR therapeutic to treat chronic lower back pain. Using the device over a 21-day period, participants experienced a significant reduction in pain outcomes.43 It’s important to note, however, that VR is not yet widely supported by existing research and remains an emerging area of study.

Pain has long been associated with substance use related to alcohol as well as nicotine and tobacco. However, such substances are not helpful in the long term. Studies show frequent or heavy use may be a risk factor for the progression of chronic pain – and attempting to stop using could result in increased sensitivity to pain in the early stages of quitting.44

Unfortunately, firsthand insight from providers reveals that self-medication with alcohol or other substances can be relatively common among injured workers, and data supports this. In an analysis of 100,000 physical therapy evaluations by Healthesystems, “substance abuse” or related terms were mentioned in nearly 8% of claims.

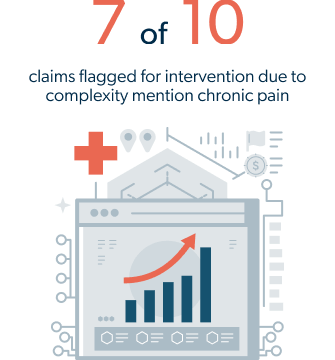

Unresolved chronic pain can become increasingly complex over time and more challenging to treat. In fact, chronic pain is a key indicator of claim complexity and the downstream impacts. These include high costs and increased utilization of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic medical treatments, such as physical therapy.

As assessed by WCRI, among comorbidities associated with high-cost claims, chronic pain is the second-most identified factor after hypertension – sitting right above psychological concerns such as anxiety and depression. What’s tricky about chronic pain, as WCRI indicates, is that it isn’t necessarily a pre-existing condition but may arise downstream during the period of injury treatment.45 When it does arise, physical therapy evaluations can be a good source for early identification.

Among approximately 100,000 physical therapy evaluations analyzed by Healthesystems, about 5% mention chronic pain. This frequency significantly increases in more complex and high-risk claims. For instance, in a subset of claims identified for a targeted intervention program for therapeutic complexity, approximately seven out of 10 claims mention chronic pain – underscoring the value of early intervention opportunities.

Thanks to the rise of data analytics and predictive modeling technology, workers’ comp organizations now have the opportunity to identify chronic pain as well as any injured worker behaviors and characteristics that could add to claim complexity. When at-risk claims are identified early, these insights can be leveraged to help address pain as a complicating factor. Possible interventions and solutions include assessing the appropriate timing of physical therapy, optimizing medication regimens, providing patient education, or even providing referrals to psychosocial/behavioral health services.