The COVID-19 pandemic depressed economic activity and decimated employment numbers to levels not seen since the Great Depression.1 The impact was felt across industries and throughout the world. But, as with all disasters, the damage was more severe for certain sectors of the population. In this case, women have been more adversely affected,2 not only by direct job losses, but also by the infrastructural impact of the pandemic, such as closing schools and daycare facilities, that made it difficult to impossible for women to manage conflicting responsibilities.

A disproportionate impact to women’s employment was apparent from the earliest days of the pandemic. In April 2020, the unemployment rate in the U.S. increased by 10.3%, bringing the total unemployment rate to 13% for men, but a considerably higher 15.5% for women.3 Black and Hispanic women suffered even greater employment losses, accounting for 46% of the total decrease in women’s employment, even though they represent less than a third of the female labor force.4

Between February 2020 and February 2021, 2.4 million women left the labor force (meaning they were neither working nor looking for work), as compared to 1.8 million men who left the labor force.5 And there is evidence to suggest a good number of those women may not come back to work, such as the 18% of employed mothers who reported to McKinsey in 2020 that they were considering leaving the workforce entirely.6

All segments of the American population were affected by the pandemic and job losses were staggering across the board, but women were particularly vulnerable to the idiosyncrasies of this particular recession for multiple and overlapping reasons, including:

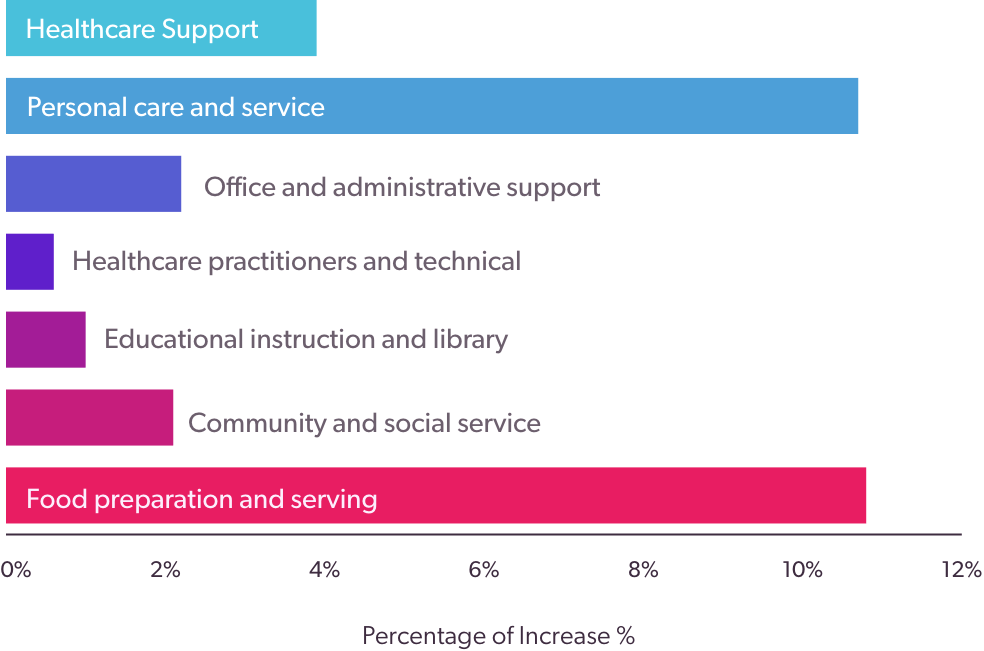

Nearly half of all women (46%) work in low-wage jobs7 where employment fell by 11.7% during 2020, as compared to 5.4% for middle-wage earners and virtually no change for high-wage workers.4

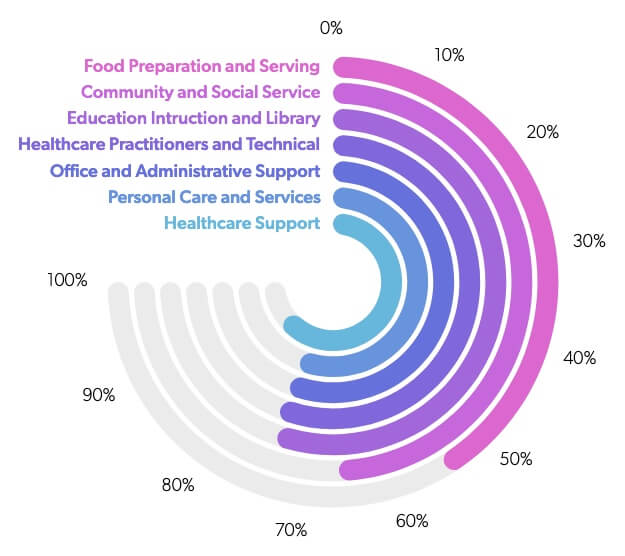

Women account for 78% of healthcare workers who were at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19 during 2020.7

Women fill the majority of service sector occupations where most of the job losses occurred.9

Childcare responsibilities: Labor force participation among women with children dropped 2.3% from February 2020 – January 2021, whereas the drop for men with children was only 0.8%.8 A significant drop in employment occurred among women with children in August and September of 2020 when home schooling began for many.9

Elder and other family care: 1 in 7 women provide care to elder or disabled relatives10 and external support, such as adult daycare, became scarce during the pandemic.

More women (62%) than men (46%) feared contracting COVID19, which may have made them more reluctant to go out to work.8

Women earn less than men for the same work – women without a bachelor’s degree make 78 cents for every dollar of their male counterparts and women with a bachelor’s degree or higher fare even worse, earning 74 cents for every dollar a man makes for similar work.11 Lower earnings provide less incentive for women to stay in the workforce, especially with competing priorities, such as child and elder care.

All of these factors combined to create a perfect storm that put more women involuntarily out of work, while simultaneously making it more difficult for employed women to do their jobs. The consequential decrease in women’s employment, even if it’s only temporary, could have resounding effects on women’s career progress, the success of individual businesses, and the U.S. economy as a whole.2

Any change to the U.S. workforce has an impact on workers’ compensation and the balance of male to female workers is no exception. The pandemic exposed issues that make women vulnerable to unemployment and work-related health risks, both of which could affect injured worker trends and patient care.

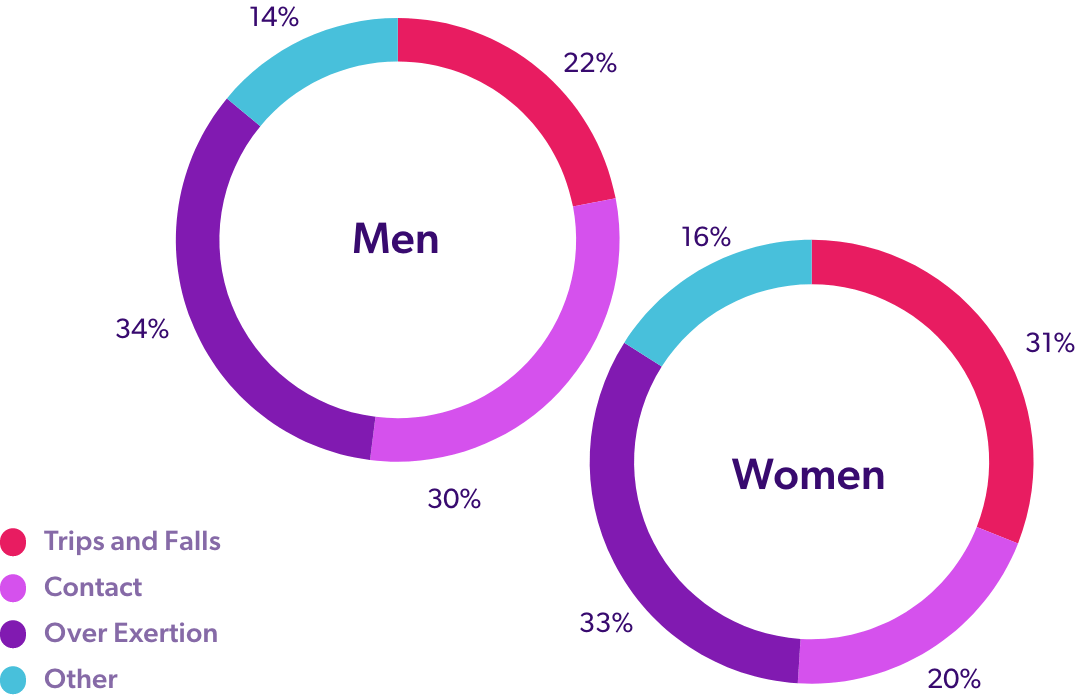

The ratio of women to men in the workforce has a direct effect on worker injury rates for a number of reasons, the first being that women are less likely to be injured on the job. Overall, women account for 17% fewer injuries than men 12 and 35% fewer injuries that involve time away from work.13 This is partly due to the fact that fewer women work in high-risk industries, such as construction and mining, but even within industry sectors men are injured at higher rates than women.12

The most common injury causes are also different for women who are more likely to be hurt slipping or falling and less likely to sustain a contact injury. Women report more work-related injuries for carpal tunnel syndrome, tendonitis, respiratory diseases, and infectious diseases.12 Overall, women’s injuries tend to be less severe, requiring an average of seven days to recover as compared to 10 days for men.14

However, women experience higher rates of depression15 and anxiety,16 the incidence of which has risen significantly since the pandemic began.17 These mental health conditions can complicate treatment and delay recovery. In addition, although men are more prone to substance abuse disorders, women are more frequently prescribed opioids and twice as likely to be prescribed benzodiazepines, both of which pose high risks for adverse drug effects. The psychosocial issues associated with injury, unemployment, and caregiving responsibilities can cause or exacerbate mental health conditions and/or lead to dependence on problematic medications.

What’s more, there is evidence that psychosocial-related medical conditions, including depression, headache, and poor sleep, are associated with the likelihood of injured women workers filing subsequent workers’ compensation claims, but not so for men.18

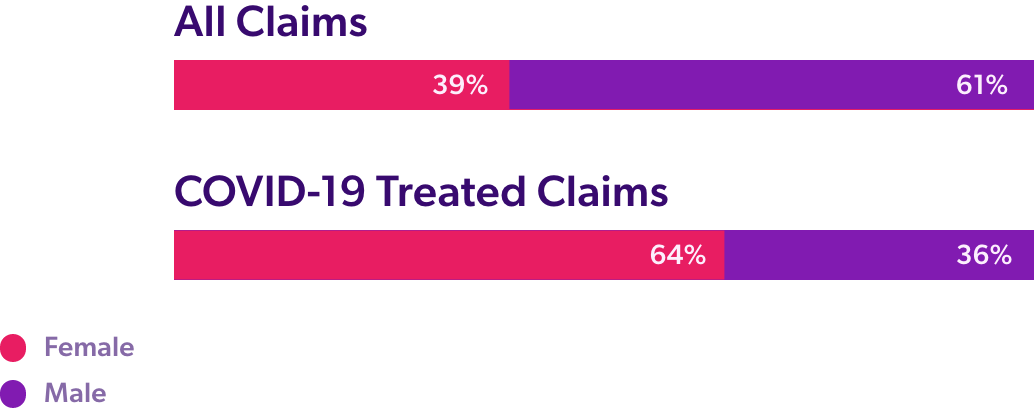

The COVID-19 virus also affects men and women differently. In the general population, men are somewhat more likely to contract and die from COVID-19 but women file significantly more workers’ comp claims for COVID-19,20 probably due to their over representation in healthcare services. Women are also more likely to suffer the effects of “Long COVID-19”21 which includes a range of symptoms, including cognitive issues and depression, that could affect recovery, not only from COVID-19 itself, but from other injuries and illnesses as well. (See The Long Haul: Chronic Health Complications of COVID-19, also in this issue of RxInformer.)

And of particular concern in workers’ compensation, female patients – who express the same intensity of pain as male patients – are perceived to be in less pain than they report, due to gender bias on the part of both male and female observers in clinical settings.22 If women injured workers pain is not accurately evaluated, it is more likely that it will not be properly treated, increasing the likelihood of depression and extended recovery time.

The potential impacts of sustained change in women’s workforce participation are many and variable. When it comes to injured worker medical care, workers’ compensation payers should be aware that patient population patterns may shift. Changing demographics, alternative work settings, increased psychosocial issues, and a virus about which much is still to be learned, all add up to an imperative for a comprehensive approach to workers’ comp medical management that includes data analytics, risk management strategies, and personalized clinical services capable of attending to the needs of injured women workers.

Whether the alterations in women’s workforce participation will be short-lived or enduring remains to be seen. However, it is clear now that the pandemic and the subsequent recession exposed vulnerabilities for working women that will continue to impact the labor force and women’s health, both of which are important concerns for workers’ compensation and injured worker medical care management.