The wide-reaching concerns posed by opioids to patient safety and claim outcomes are well understood within workers’ compensation, and we have implemented many effective measures as an industry to tackle the opioid challenge. These efforts have been further bolstered by broad federal and state-based legislation that has occurred over the past several years, contributing to positive outcomes on a national level, including reduced prescribing rates and lower average morphine equivalent dose (MED).1

However, like most challenges facing our industry, there are nuances to consider that can lend further insight into our continued assessment of opioid utilization and risk among injured worker populations.

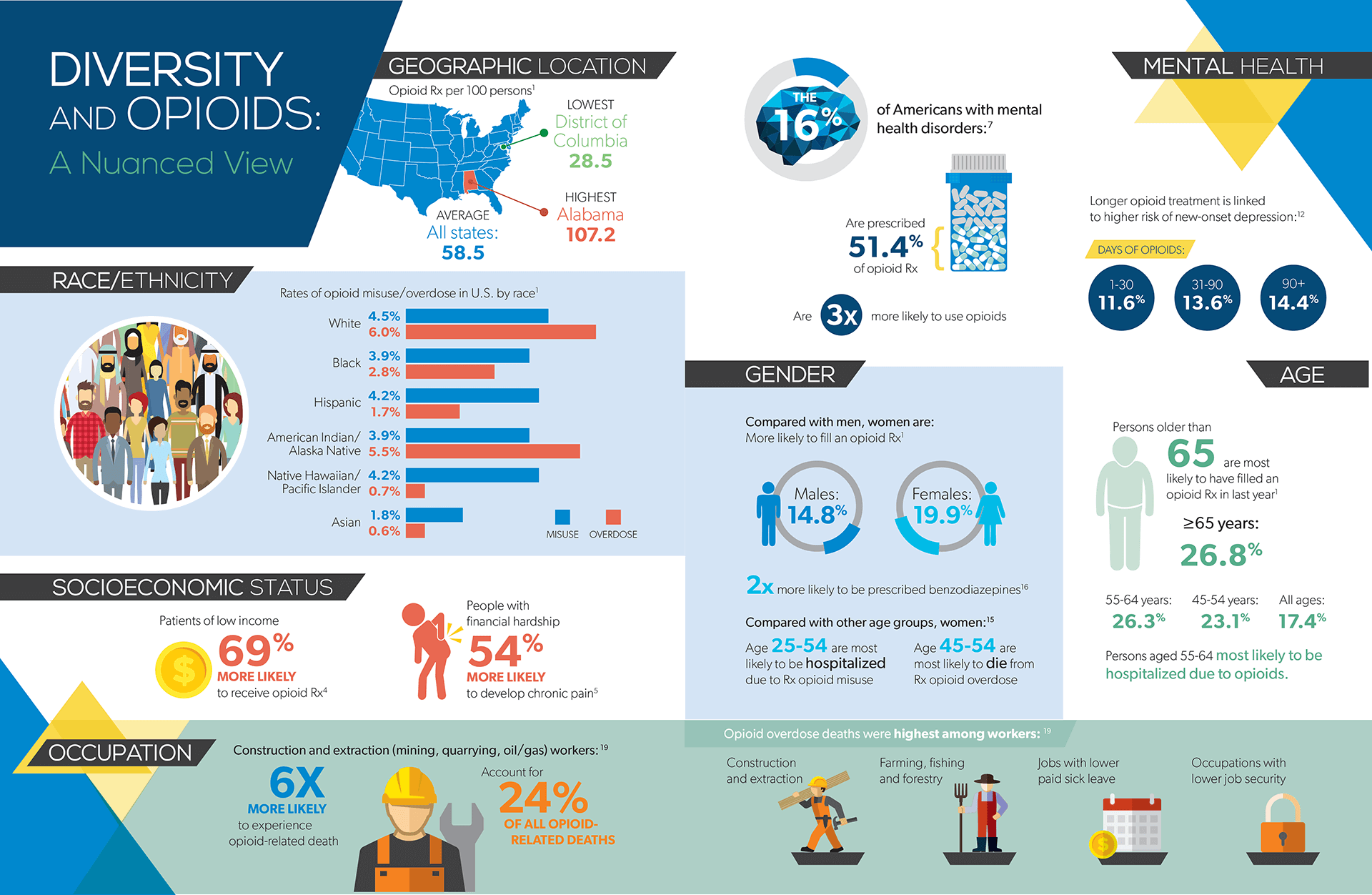

Diverse factors within populations such as patient race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographic location, age and gender, mental health status, and even occupation bring forth differentiated findings as they relate to opioid prescribing behaviors and patient outcomes. Simply put, while opioids pose a risk in some form or fashion to all patients – this does not necessarily occur on an “equal opportunity” basis.

The relationship between race/ethnicity and opioids is complex and evolving. Historically, trends have shown racial disparities in pain management, and specifically in the opioid prescribing behaviors of doctors. Until recently, non-Hispanic white patients were more likely to be prescribed opioids and faced higher risk for prescription opioid overdose. However, a national trends study published in June indicates that the gap has closed between whites and blacks in regard to opioid prescribing for noncancer pain.2

While eliminating treatment disparity represents positive movement from a public health equality perspective, increased prescribing of opioids among black patients has created some negative consequences that include increased rates of opioid misuse within this population. While self-reported prescription opioid misuse remains highest among the white population at 4.5% nationally, other race/ethnic groups including Hispanic (4.2%), native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (4.2%), and black (3.9%) populations are now proportionally very close from a risk perspective. However, non-Hispanic white individuals are still twice as likely to die from prescription opioid overdose compared with non-Hispanic black individuals.1

In addition to these shifting dynamics, interrelationships between race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and geographic location add to the complexity when analyzing population-based risks.

The opioid crisis has disproportionately impacted poorer regions of the country, and lower-income individuals are twice as likely to have an opioid use disorder.3 This has partly been attributed to reduced accessibility to quality healthcare. A 2017 study reported that patients of low socioeconomic status were 63% more likely to be prescribed an opioid for low back pain by their primary care doctor, and more generally tend to be at increased risk of receiving care that does not comply with evidence-based guidelines.4

However, there are other factors at play that go beyond access to care. For example, individuals who have experienced financial hardship are 54% more likely to develop chronic musculoskeletal pain,5 which in turn may contribute to higher rates of opioid prescribing. And individuals who are surrounded by a stressful environment or lack a socially supportive network – which are often products of, but not necessarily specific to, low socioeconomic status – are at increased risk for substance use disorders, including opioid use disorder.

In many ways, socioeconomic status and geographic location are tightly interwoven in their relationship to opioid risk, as evidenced by the impact among poorer regions of the United States, including clusters within Appalachia, the South and the West. Geographical analysis indicates a strong relationship between poverty rates and unemployment rates with higher opioid sales and overdose fatality rates.2

But there are other geo-factors to consider that can influence opioid risk. Sparse populations in rural areas can contribute to feelings of isolation, a psychosocial factor associated with increased risk for opioid misuse. Prescriber behaviors also geographically influence risk, as prescribing practices vary across the U.S., often regionally. Previous analyses have consistently found that doctors in the Northeast and Midwest are much less likely to prescribe opioids compared with their Southern and Western colleagues.6

Psychosocial factors may arguably be the most powerful risk predictor for opioid utilization, misuse, and addiction,7,8 and thus prescribing in this population brings an added layer of complexity warranting additional caution and increased monitoring. Yet more than half the opioids in the U.S. are prescribed to adults with mental health conditions.7

In workers’ comp, this is of special concern because injured workers face higher rates of select psychosocial disorders such as anxiety, depression and helplessness.9,10 Often these conditions are not directly related to the injury, but can develop after the injury has occurred as the injured worker faces challenges such as a reduced quality of life, financial stress, feelings of isolationism, and the inability to perform certain job functions or even to participate in work at all. One out of every five individuals who have incurred moderate-to-severe injury will develop a psychosocial disorder within one year.11

Conversely, opioids play a direct role in the development of psychosocial disorders, specifically depression. More than 10% of patients receiving opioids for the first time will develop new–onset depression within the first 30 days – and this risk only increases with longer treatment durations.12

It may be surprising to learn that older adults are prescribed opioids more often than any other age class. In 2017, more than 26% of persons aged 55 or older filled an opioid prescription, the highest of any age group, and markedly higher than the 17.4% of the overall U.S. population that filled an opioid prescription. Individuals aged 55-64 also face the highest risk for opioid-related hospitalization.1 This may not be as surprising when considering metabolic changes and other factors related to biologic aging that may increase susceptibility to opioid adverse effects. But what is less often considered are the differences in biologic age vs chronic age. Younger patients with comorbidities or other health factors such as smoking, obesity, or hypertension may be at higher risk for opioid adverse effects than their older, but healthier, counterparts.

Why is increased age an important topic in workers’ comp? The median age of the U.S. worker continues to increase, inclusive of industries that contribute to high rates of work-related injury. Construction, agriculture, manufacturing, and healthcare services are among the industries in which the median employee age is 42 years or higher.13 And by 2024, a projected 41 million workers will be aged 55 or older.14 (For more information on the aging workforce, read “Valuable Assets: Appreciation and Care Considerations for Older Workers” in the Summer 2018 edition of RxInformer)

Based on the most recent national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it would appear that men are at higher risk for negative opioid consequences. Rates of misuse, hospitalization and overdose are higher for males across the U.S. population.1 However these data are inclusive of individuals as young as 12 years of age and include illicit use – therefore representing two components that do not factor heavily, if at all, into the workers’ comp context. When considering it through the lens of the U.S. workforce, the picture begins to shift. The age group in which women are most likely to be hospitalized due to prescription opioid misuse is 25-54,15 and women between the ages of 45 and 54 are more likely than women in other age groups to die from prescription opioid overdose16; both fall within age ranges that represent a significant portion of the workforce.

Women overall are more likely to be prescribed an opioid,1 and are twice as more likely to receive a benzodiazepine,17 which significantly increases the risk for adverse effects when combined with opioid therapy. From a biologic standpoint, research has demonstrated that women are more likely than men to:

It may not be surprising to consider that job types and industries associated with higher risk for severe injuries are also associated with higher opioid utilization – and are therefore at higher risk for opioid misuse and overdose. However, a recent landmark study conducted by the Massachusetts Department of Health revealed there are other factors in relation to a worker’s occupation that come into play. In addition to key findings around significantly increased risk for opioid-related death among industries that included construction, farming, fishing, forestry and hunting, and transportation and warehousing, higher overdose risk was also associated with occupations offering lower pay, lower availability of paid sick leave, and lower job security.19

The last two factors may point to the pressure placed on an employee to continue to work while injured or in pain, which could contribute to increased use of opioids. Additionally, overwork can contribute to fatigue or other factors that increase the potential for workplace injuries that will lead to the prescribing of opioids. The National Safety Council reports that 69% of employees are tired on the job, many of them in safety-critical jobs such as transportation, construction, and utilities.20

While industry data can provide much insight into potential risk factors, as noted above, certain factors in the broader population can influence trends in a manner that is not consistent with the injured worker population. Advanced analytics can be applied to help identify risk factors more specifically among workers’ comp claim populations, as well as tie them more directly to measures of opioid risk that are used commonly within the industry to invoke intervention opportunities, such as morphine equivalent dose (MED). Healthesystems analyzed 40,000 claims over a five–year period to develop a model that could help estimate probable risk for high MED levels.21 In addition to medication-related factors such as average days supply and brand vs generic drugs, factors that presented the highest level of risk included:

GENERATION X SEGMENT

(ages 38-55 years old)

LOW INCOME

AGRICULTURAL OCCUPATION

These findings are largely consistent with broader trends, but nuances may shift from population to population, depending on the injured worker mix.

While using advanced analytics to conduct population analyses can provide a more nuanced understanding of opioid risk among injured worker populations, effective patient management boils down to this: is the patient getting what she or he needs? This includes receiving appropriate, evidence-based treatment for their injury or illness, while taking important patient-specific factors into consideration. It also means ensuring that everyone involved in that treatment – the doctors, the pharmacists, the patients themselves – have the information they need to be educated participants. How or when these needs are delivered and managed may simply look a bit different from claim to claim depending on the individual circumstances of an injured worker and how his or her claim progresses. To accommodate this, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Ultimately, the more controls and intervention opportunities that can be created to help manage an injured worker from the moment they fill a prescription, the more opportunity there is to course-correct along the way to ensure that each individual worker is getting what they need, when they need it.