Off-label prescribing may include any scenario wherein a physician prescribes a medication in a way that differs from the product label. This can apply to a variety of circumstances, such as: prescribing for a condition other than the FDA-approved indication; recommending a dosage or treatment duration outside the indicated parameters; introducing a medication at the wrong time in a patient’s treatment course, or; changing the method of administration.

Certain medications are commonly used off-label in workers’ comp. Sometimes this approach is medically warranted and may benefit the patient. But in many cases it is clinically inappropriate, can present risk to the patient, and may be cost-ineffective.

What are the potential upsides and downsides of off-label prescribing from a treatment standpoint in workers’ compensation, and how can it impact medical costs? What are some considerations for claims management?

The most commonly recognized form of off-label prescribing is when a drug therapy is used to treat a medical condition for which the FDA has not approved its use.

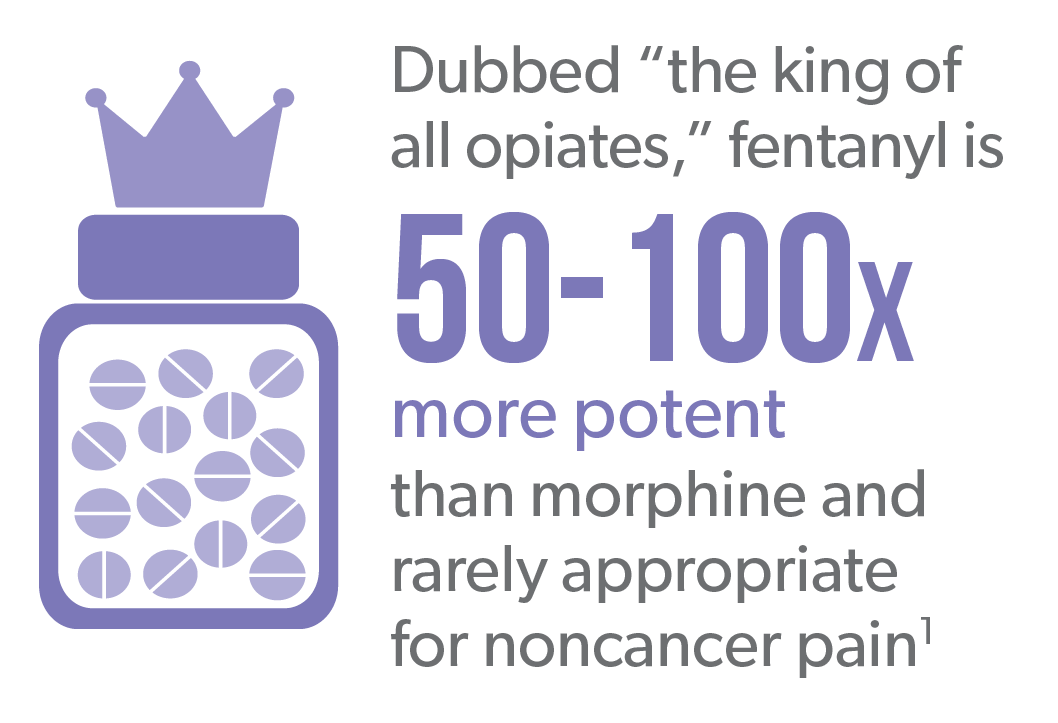

Fentanyl is a potent and highly addictive opioid that has a history of being prescribed off-label in workers’ comp. Products such as Actiq® (fentanyl “lollipop”), Fentora® and Subsys® are exclusively indicated for use in breakthrough cancer pain.2-4

Yet they have been prescribed to injured workers for noncancer back or neck pain. This practice has declined in recent years due to increased scrutiny.

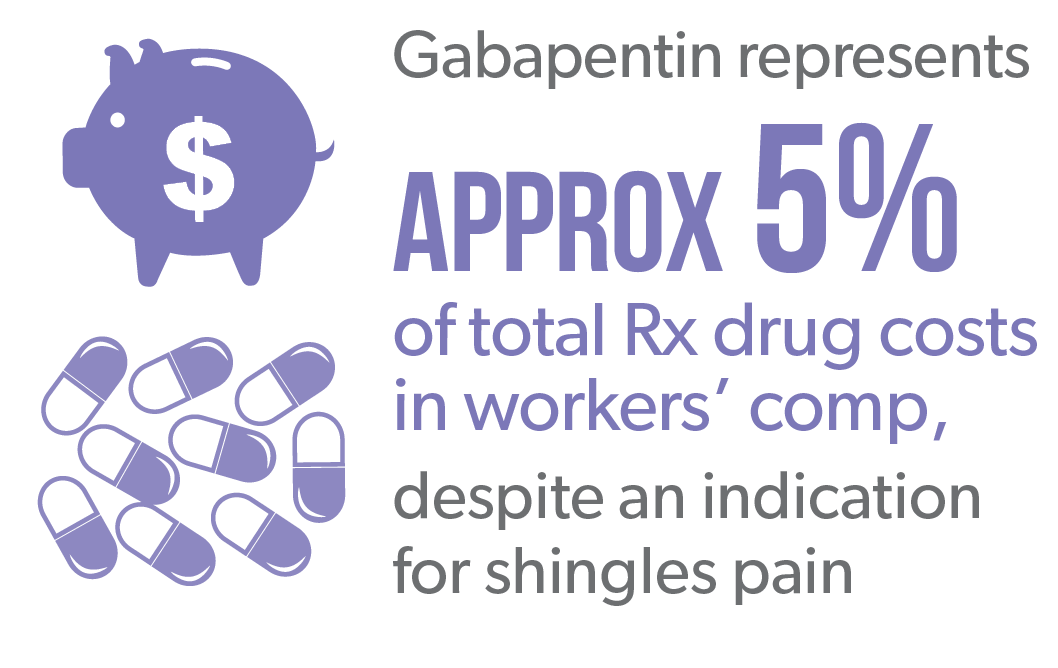

Antiepileptic (anti-seizure) drugs (e.g., pregabalin, gabapentin) are also effective in treating certain types of neuropathic pain because of how they affect nerve activity. Gabapentin is FDA-approved to treat shingles pain specifically, but in workers’ comp, it is prescribed off-label for other types of neuropathic pain.

Gabapentin has historically been in the top prescribed drugs in worker’s comp and represented 4.7% total pharmacy costs in 2014.5 Lyrica® (pregabalin), which is indicated for nerve pain associated with shingles, diabetes and spinal cord injury, is also prescribed more broadly in workers’ comp. Lyrica contributed to 5.5% of total pharmacy costs in 2014, second only after OxyContin®.

Medications that are effective via one route of administration may not be effective via a different route of administration.

Topical compounds often contain ingredients that are FDA-approved for oral use only. This pertains to a number of drugs, including most non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Apart from diclofenac, which has been approved for topical use, there is little evidence that NSAIDs are efficacious when applied topically. Thus, these ingredients can add excessive cost without providing benefit to the patient.

Gabapentin has historically been in the top prescribed drugs in worker’s comp and represented 4.7% total pharmacy costs in 2014.5 Lyrica® (pregabalin), which is indicated for nerve pain associated with shingles, diabetes and spinal cord injury, is also prescribed more broadly in workers’ comp. Lyrica contributed to 5.5% of total pharmacy costs in 2014, second only after OxyContin®.

Certain medications commonly prescribed in workers’ comp are given at much higher doses or for much longer durations than recommended in the product label, often providing no additional benefit with increased adverse effects.

Muscle relaxants (e.g., carisoprodol, cyclobenzaprine) are intended for short-term relief of discomfort associated with acute, painful musculoskeletal conditions.6 But they often prescribed for much longer than the recommended 2-3 weeks stated in the product label.

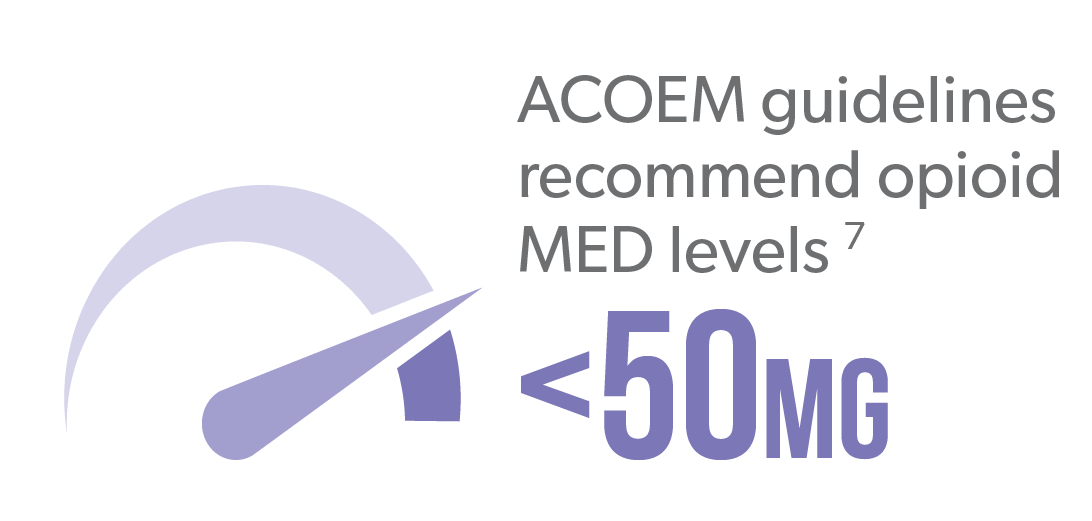

Opioid product labels, as well as evidence-based guidelines, recommend opioids be prescribed at the lowest effective dose. Yet many patients continue to receive very high doses of opioids over the long-term, even though

long-term efficacy of opioids for noncancer pain is unproven. Meanwhile long-term opioid therapy is associated with increased risk of dependence or abuse,8 and there is a dose-dependent effect on fatal and nonfatal overdose.9,10

Very often, drugs are prescribed in workers’ compensation in a manner that doesn’t adhere to the product label’s warnings or contraindications, presenting significant safety risk to the patient.

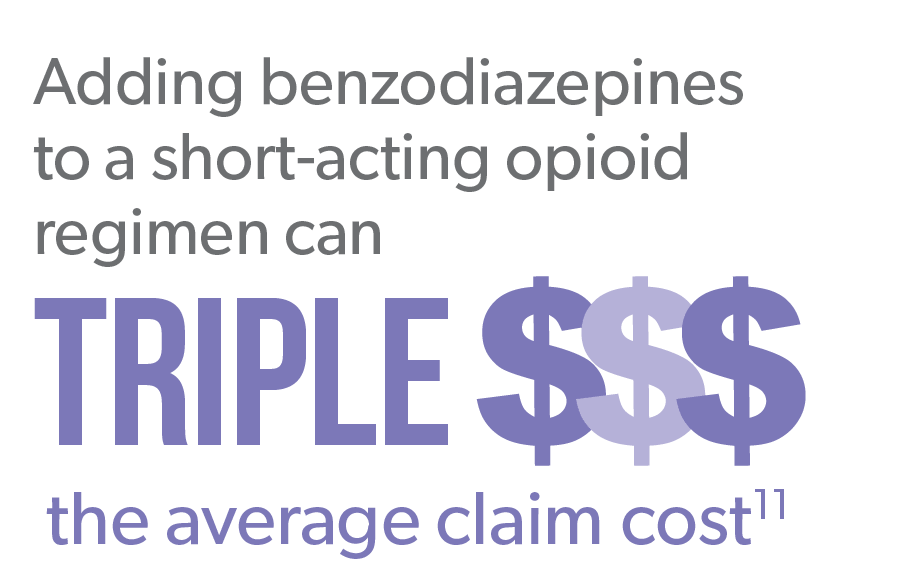

Benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam, diazepam) are antianxiety medications commonly prescribed in conjunction with opioid therapy, despite the fact many opioid product labels contain a Boxed Warning specifically warning against co-prescribing of these two medication classes due to risk of respiratory depression, coma, or death.

This describes prescribing a medication at the wrong time in treatment (e.g., using a second-line agent as first-line). It can also include prescribing a therapy as a single agent when it is only approved as adjunct therapy, and therefore not effective enough on its own to treat a given condition.

Abilify® (aripiprazole) is an atypical antipsychotic approved as an add-on treatment for major depressive disorder. In workers’ comp, it is often used off-label as a single-agent therapy to address depression, anxiety, or insomnia, despite availability of more appropriate single-agent therapies.

Extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) opioids like OxyContin® (oxycodone HCl) are typically indicated only after failure of alternative primary treatments to adequately manage pain, but are occasionally prescribed as first-line agents before pharmacological and nonpharmacological alternatives are adequately explored. ER/LA opioids present increased risk for dependence, addiction, and misuse.

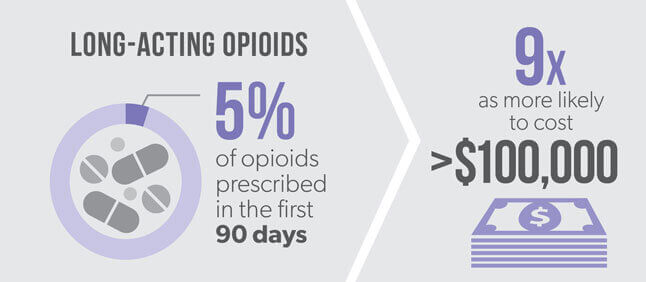

Despite their indication as later-line therapy, in claims >1 year, 5% of opioids prescribed in the first 90 days post-injury were long-acting.12 Even a small percent can significantly impact cost. Claims with long-acting opioids are 9x as likely to cost more than $100,000 than claims without opioids present.13

In overall patient management, off-label prescribing can be an important component of treatment. Patient care is a very individualized process, and there are circumstances where patients can benefit from the application of a drug therapy that hasn’t been approved for their given condition.

Preeminent treatment guidelines recognize the need to allow for off-label use when medical circumstances require it. The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) acknowledges the need to allow prescribers this flexibility when standard treatments have failed or are contraindicated, so long as they are able to provide compelling clinical rationale.14 Similarly, the Official Disability Guidelines (ODG) support instances of off-label prescribing when accompanied by evidence of the medication’s effectiveness.

In workers’ compensation, however, many common off-label prescribing practices are a detriment to patients’ health and recovery. In these scenarios, at best the prescribed medications are ineffective, failing to benefit the patient while adding directly to healthcare costs. At worst, they add adverse effects, worsen the patient’s condition, and add more significantly to overall medical costs as additional treatments and interventions are required to address these new or exacerbated concerns.

This is especially relevant when it comes to high-risk drug therapies such as opioids, benzodiazepines, and muscle relaxants. Prescribers cannot apply loose parameters to drugs that require strict management parameters and high levels of oversight.

In some cases, it may come down to a lack of awareness or misinformation among prescribers. Drug makers have been increasingly aggressive with their tactics to promote and encourage off-label prescribing. And while these tactics have historically been tightly regulated by the FDA, there is the potential for this position to change.

There can be a fine line dividing off-label prescribing and drug diversion, and that line is typically defined by intention.

Treatment guidelines give prescribers the flexibility to treat off-label if the prescriber believes it’s in the patient’s best interest. But if the intention is profit over patient safety, off-label prescribing can fall into the category of drug diversion, or the redirection of prescription drugs for illegitimate purposes.

A number of manufacturers of opioid medications have been under fire within recent years due to aggressive marketing tactics for off-label use. Perhaps most notably, the makers of Subsys, a powerful fentanyl nasal spray indicated for breakthrough cancer pain, are facing ongoing federal investigation and criminal charges for promoting the product for unapproved uses that include migraines and neck pain.15

In some cases, off-label communications can provide misinformation to a well-intended prescriber or pharmacist, as well as the end consumer, the patient. In other scenarios, the prescriber or pharmacist is implicit in the drug diversion. Investigations into Subsys revealed that the drug manufacturer financially incentivized top prescribers of the product, which have been characterized as kickbacks by multiple state governing bodies.

Such actions raise concerns about the potential for the FDA to loosen regulation regarding the promotion of off-label drug use.

The FDA has traditionally held very strict parameters around what information drug manufacturers can promote about their products. Traditionally this information has had to adhere to the product label. But the FDA is currently engaged in a review of the regulatory framework related to manufacturers’ communications regarding unapproved uses of medical products, including drug therapies. In late 2016, the FDA held a public hearing to receive input on manufacturer communications regarding unapproved uses of medical products. The comment period was then extended until April 19, 2017.

While drug manufacturer communications can meet an important need in communicating drug information to prescribers and patients, these communications become dangerous when they promote unsafe prescribing practices. (See Sidebar: Off-Label Prescribing or Drug Diversion?)

The increased scrutiny and regulation surrounding off-label prescribing over the last decade has garnered positive results. Notably, the fentanyl “lollipops” that were rampant in workers’ compensation populations in the mid-2000s are no longer such a prevalent problem. Much of the success can be attributed to tighter clinical management as well as policy interventions. Some state workers’ compensation boards have established regulations to reduce off-label medication use. And the application of state drug formularies can help curb the problem by not including “problem” drugs – drugs that are commonly prescribed off label or otherwise inappropriately prescribed – from the formulary.

The forthcoming California DWC formulary, for example, does not include opioids and muscle relaxants on its list of preferred drugs, in an effort to encourage prescribers to apply first-line, preferred medication alternatives.

From a claims management perspective, identifying off-label prescribing in a workers’ compensation patient profile can be difficult, especially when it’s unclear what a particular medication is being prescribed for. But pharmacy management strategies don’t have to focus specifically on whether a product has been prescribed “off-label” to be effective. Most importantly, they should address these questions: Is the therapy clinically appropriate for a particular patient and their condition or injury? Is it cost-effective? Ultimately, evidence-based medicine must guide clinical decision-making. Working closely with a pharmacy benefit manager and having the right amount of clinical decision support can help answer those questions to ensure safe and effective care.

Sometimes, this can be obvious. A patient experiencing pain from a shoulder injury should not be receiving Actiq®, a powerful fentanyl product approved for cancer pain.

Other times, it is harder to determine. For example, tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline are sometimes prescribed off-label to treat neuropathic pain. It can be unclear in a patient profile which condition the drug is being prescribed for – the pain, or depression.

Some drugs commonly prescribed in workers’ comp are not approved for use (contraindicated) in patients with certain comorbid conditions. For example, because a serious side effect of opioids is respiratory depression, opioids are contraindicated in patients with breathing disorders.

Certain drugs have very clear language in their prescribing information about approved duration of therapy. For example, the prescribing information for muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril®) and carisoprodol (Soma®) state these medications should only be used for up to 2-3 weeks. In reality, they are often prescribed for much longer periods of time.

Black Box Warnings exist in the prescribing information for opioids and benzodiazepines (alprazolam, diazepam), warning of the life-threatening risks of combining these two medication classes. Yet they are still one of the most common drug combinations prescribed in workers’ comp.

For a list of common medications in workers’ comp and their FDA-approved uses, visit the Medication Guide, or download the Healthesystems app.