The U.S. workforce continues to change. Millions of workers grow older, remote work is more common, and worker priorities have changed. And when the workforce evolves, aspects of workers’ comp can be impacted – whether downstream impacts on timing and access to care for the injured worker, or the ways in which claims organizations

must adjust and strategize for their own staffing challenges to continue operations running smoothly and effectively.

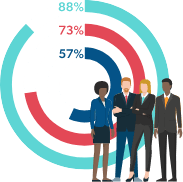

Based on results from Healthesystems’ 2022 Workers’ Compensation Industry Insights Report, workers’ comp professionals now view the changing workforce/workplace as the number one factor impacting resiliency in workers’ comp, with 71% of workers’ comp professionals ranking the changing workforce as their top industry concern.1

Workforce trends have always trickled down in some way to employee populations, and subsequently, workers’ comp. But in a world changed by COVID-19, a new movement has entered the picture – the Great Resignation – with employees voluntarily resigning from their jobs in mass waves. Millions of Americans are leaving their jobs, with some industries losing significant portions of their workers.

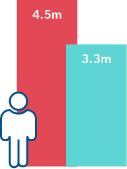

4.5 million

Americans quit their job in November 20212

3.3 million

quit in November 20202

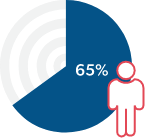

are looking for new jobs3

57% believe attracting talent will be a challenge4

While there is no single reason why workers are leaving their jobs, the pandemic has contributed several reasons and exacerbated others.

Different industries are facing different types of challenges, but pandemic-related factors and mass resignations play a role in some of the biggest hit industries, including healthcare, the food service industry, the supply chain, and the public sector.

Healthcare workers have likely been hit the hardest by the pandemic. While proper PPE can protect healthcare workers from COVID-19, their proximity to COVID-19 patients does increase their likelihood of viral exposure, creating concern. Furthermore, the pandemic has also made difficult jobs even more stressful.

The influx of COVID-19 patients into hospitals over the course of the pandemic has presented a strain to both healthcare workers and resources. Not only are these workers burnt out, but when some of them quit, the ones remaining are left to pick up extra responsibilities. Additionally, some medical programs may have been placed on hold during the pandemic, slowing the introduction of newer healthcare professionals.

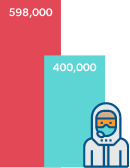

598,000

healthcare workers quit their jobs in November 202111

400,000

quit in November 2020

Total net jobs in healthcare decreased 450,000 since February 202012

1 in 5 healthcare workers quit their job since the pandemic started13

Even before the pandemic, there was an impending shortage of healthcare workers on the horizon, and the Great Resignation can only exacerbate this problem:

30% of physicians retire between 60 and 6514

The average nurse is 5115

Pre-pandemic, it was estimated there would be a physician shortage of

47,000-

122,000

providers14

Home health aides are

projected to be the most in-demand occupation over the next decade16

Workers in the food and hospitality industry must regularly work next to large numbers of the general public, and fear of viral exposure has pushed many to quit their jobs.

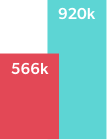

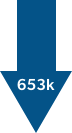

Quit rates in the food and accommodation industry increased from 566,000 in November 2020, to 920,000 in November 2021.11 Total net jobs in the food and accommodation industry decreased 653,000 since February 2020.17

But fear of sickness isn’t the only thing keeping these workers from returning. Many food service workers were initially laid off at the start of the pandemic, and while some of these workers were able to return, many left the industry altogether. Furthermore, growing economic pressures spurred by the pandemic could be driving these workers to seek other industries that offer greater pay.

The pandemic significantly impacted the supply chain in a variety of ways. Online orders increased as people grew reluctant to visit stores in-person and purchased more home goods, creating greater demand. Meanwhile, workers getting sick created a labor shortage both directly from sick workers needing time to recover, and indirectly from workers leaving their roles due to fear of viral exposure.

Training schools for truckers offered fewer classes due to the pandemic, older workers are retiring – the list goes on.

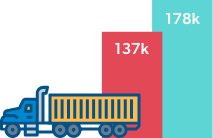

Quit rates in the transportation, warehousing, and utilities industry increased from 137,000 in November 2020, to 178,000 in November 2021.11 The trucking industry alone faces a historically high shortage of 80,000 drivers.18

Public service workers have also seen declines in their worker populations.

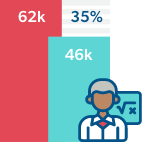

The education industry saw monthly quit levels increase from 46,000 in November of 2020 to 62,000 in 2021,11 a 35% increase. Teachers are concerned with COVID-19 exposure when working with classrooms full of students who may or may not be vaccinated. Furthermore, many teachers must conduct in-person lessons in addition to virtual lessons in many scenarios. The added stress is pushing many to leave the profession.

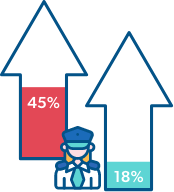

Law enforcement has also seen greater quit levels. Across the country, there was a 45% increase in retirement rates and an 18% increase in resignation rates from 2019-2020.19 In addition to pandemic concerns, current rhetoric and negativity surrounding law enforcement is lowering morale and leading to more resignations, while also creating a negative impact on the number of new recruits.19 And with fewer officers available to cover shifts, remaining officers are working longer shifts, increasing overall fatigue.

Even before the pandemic, the workers’ comp industry faced an impending talent shortage and now that problem has grown worse. Two of the hardest-hit roles happen to be two of the most crucial roles at claims organizations: claims adjusters and IT specialists.

While there are some universal solutions a workplace can offer to attract and maintain employees – such as competitive compensation and benefits – there are industry-specific matters that workers’ comp must address.

As the workforce continues to shift with some industries losing or gaining workers, here are some potential impacts in workers’ comp to consider.

The shortage of healthcare workers can impact the availability, timing, and quality of care for injured worker patients. One area of note is the dearth of home health nurses, underscoring the importance for depth, strength and quality of ancillary medical networks.

Home health aides are projected to be the most in-demand occupation over the next decade,16 and without home health nurses, home care agencies have had to deny referrals. As a result, patients requiring home care are either remaining in the hospital or risking injury without the assistance they need.

With workers leaving certain industries in droves, the workers that remain may have to work greater hours and face increased pressure. This could lead to fatigue, which increases the likelihood of workplace injury:

While it is too early to deliver any numbers on this matter, it is a possibility that as certain industries gain or lose employees, the frequency of certain occupational injuries and illnesses could change.

For example, in 2019 there were 93,800 nonfatal injuries and illnesses in full-service restaurants, with these workers experiencing over six times as many burn injuries and over three times as many cuts and lacerations than the rest of the workforce.24

However, quit rates in the food industry increased 62% from 2020 to 2021,11 with an overall net decrease of 653,000 jobs since February 2020.17 With fewer workers in this industry, it is likely these types of injuries may decrease as a share of claims. While it remains to be seen what specific shifts in illnesses and injuries may occur, it is certainly something to consider.