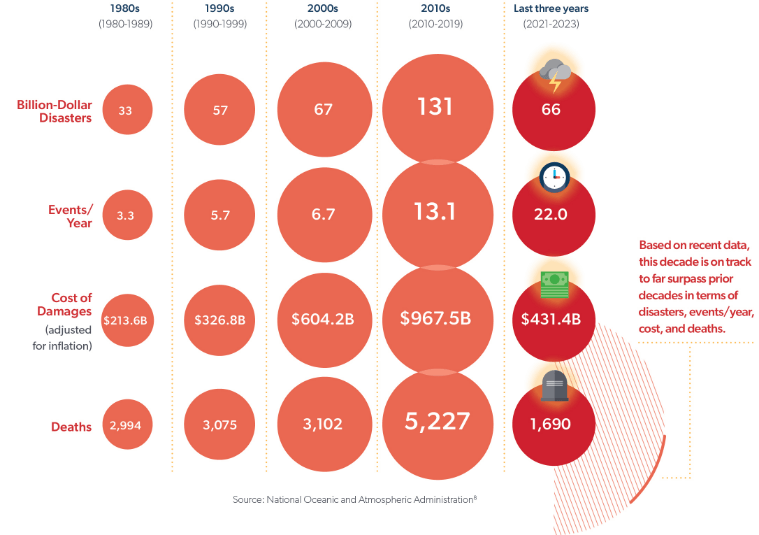

In 2023, 28 distinct billion-dollar weather events hit the United States.1 Compare that to an average of just 13.1 events per year in the 2010s and 6.7 in the 2000s.2

The World Health Organization describes climate change as “the biggest health threat facing humanity,” while the World Economic Forum names extreme weather events as the top risk global populations will face over the next 10 years.3 In fact, the direct damage costs to health due to climate change are estimated to be between $2 and $4 billion per year by 2030.4

While climate change affects everyone, certain workers – coined as “climate canaries” by the American Journal of Public Health5 – are especially vulnerable. These include outdoor workers, indoor workers in hot environments, and emergency response workers. Depending on the type of weather event, these workers may suffer anything from heat illnesses to respiratory illnesses to physical and mental health effects – any of which can lead to injury or death.

In workers’ compensation, climate change remains a top-of-mind issue for insurance executives.6 Plus, occupational injuries and fatalities due to climate change are increasing. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries shows that fatalities due to temperature extremes increased 18.6% in 2022.7

While working conditions are largely under the control of employers, workers are vulnerable to climate hazards because they may not have access to necessities like adequate drinking water, sunscreen, protective garments, rest, and shade. Many large employers implement safety programs and training for their workers to mitigate climate hazards. However, many more small and mid-sized employers do not have such programs in place.

Let’s look at a few types of major weather events and how they impact workers, as well as the state of laws and regulations protecting workers from climate change.

By one estimate, there are over 65 million U.S. workers ages 19-64 in occupations at increased danger for climate-related health risks, accounting for over four in 10 workers.10 The worker populations who are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change include:

Many climate-related hazards11 threaten workers’ health, with health risks including:

Tropical cyclones, or hurricanes, represent 16.5% of the billion-dollar weather events since 1980. And though they are not the highest frequency type of event, they have caused the most damage and have the highest average event cost (at $22.2 billion per event).12

Hurricanes bring wind speeds of 74 miles per hour or more and present a variety of safety risks for response and cleanup workers, including physical, chemical, ergonomic, biologic, radiologic, psychological, and behavioral health hazards. Common hazards may include air pollutants, electrical hazards, extreme temperatures, falls, fire, carbon monoxide, and injury.

From 1992 to 2006, an estimated 72 fatal occupational injuries in the United States were from hurricanes, with about 40% of those involving recovery workers.13 During Hurricane Ida, which made landfall in Louisiana in 2001, 4.4% of the 91 fatalities were work related.14

Tropical cyclones, high winds, and heavy rain often lead to flooding, which makes up 11.7% of the billion-dollar weather events since 1980.15 Flooding risks for workers include infectious diseases, electrocution, falls, chemical exposures, physical hazards, poisoning, and biological hazards. Between 1992 and 2006, there were 62 fatal occupational injuries due to floods, with nearly half of the deaths occurring to passengers in motor vehicles.16

And the health effects of hurricanes and floods are not always immediate. According to a study which collected 33.6 million U.S. death records from 1988 to 2018, hurricanes and other tropical cyclones in the U.S. were associated with up to 33.4% higher death rates from several major causes in subsequent months. Researchers found the largest overall increase in the month of hurricanes for injuries, with increases in death rates in the month after tropical cyclones for injuries, infectious and parasitic diseases, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and neuropsychiatric conditions.17

Extreme heat is top of mind as heat waves become a more common occurrence. In fact, 2023 was the warmest year since global records began in 1850 by a wide margin.18 Drought makes up 8.2% of the billion-dollar weather events since 1980, with associated deaths being the result of heat waves.19

Among workers – in both outdoor settings and indoor settings where air-conditioning is not adequate – heat-related illnesses are a real risk. Heat stroke is the most serious and can cause permanent disability or death. According to one report, there are approximately 120,000 occupational injuries per year due to extreme heat in the United States. By 2050, that number is expected to increase to almost 450,000.20

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that from 2011 to 2019, environmental heat cases resulted in an average of 38 fatalities per year and 2,700 cases with days away from work. Furthermore, between 2015 and 2020 the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) conducted approximately 200 heat-related inspections per year, with about 15 heat-related fatality inspections annually. However, OSHA notes the total number of heat-related fatalities may be underreported, as the cause of death is often listed as a heart attack rather than exposure to a heat-related hazard.21

Heat-related deaths are especially prevalent among U.S. construction workers. In an American Journal of Industrial Medicine study, they accounted for 36% of all occupational heat-related deaths from 1992 to 2016 – despite comprising only 6% of the total workforce.22 Other occupations with a high risk index in the study included cement masons, roofers, brick masons, and heating, air conditioning, and refrigeration mechanics.

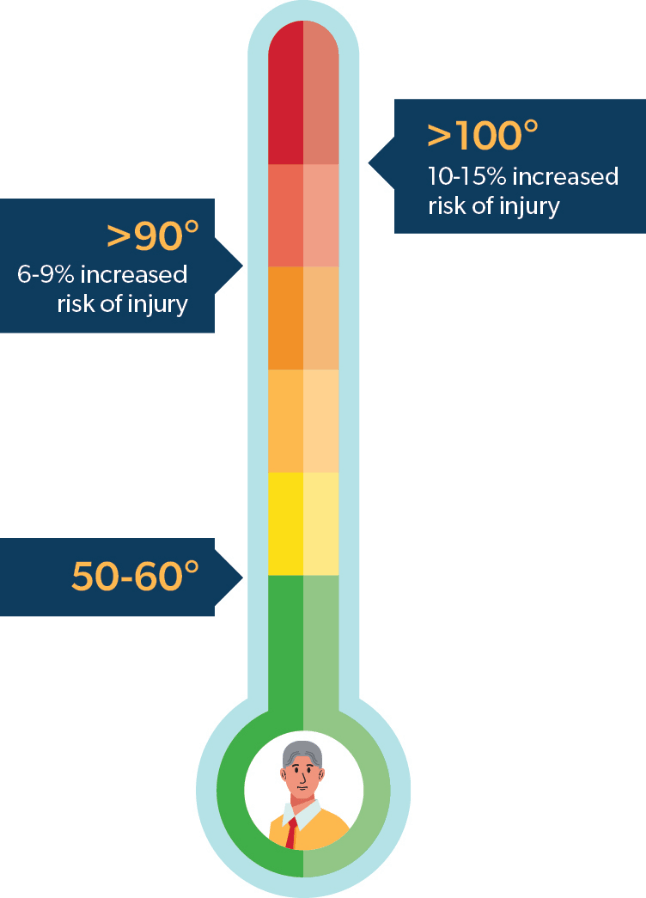

Studies also show a correlation between high temperatures and workers’ comp claims. Each year, approximately 1,000 California workers submit workers’ compensation claims for heat-related illnesses from occupational heat exposure.23 And according to a study of these claims, workers have a 6 to 9% higher risk of injuries on days with high temperatures above 90° F than they do on days with highs in the 50s or 60s. When temperatures top 100° F, the risk of injuries increases by 10 to 15%.24

Another study of workers’ compensation injury rate data from Texas found that a day with temperatures above 100° F increased workers’ compensation claim rates for the same day by 7.6 to 8.2%, and over the next three days by 3.5 to 3.7%. The commonly claimed injuries included heat exhaustion and heat stroke.25

And in North Carolina, a study reveals a positive correlation between the annual number of hours with a heat index above 90° F and workers’ compensation claim costs for lost wages. This correlation was notably strong in the cartage/trucking industry.26

Extreme heat has even become a bargaining chip in labor negotiations. In July 2023, UPS reached a tentative agreement with 340,000 of its unionized workers to get its big box trucks air-conditioned by 2024.27 This move came after at least six UPS drivers in the New York City region suffered heat-related illnesses during a week-long heat wave in 2022.

Though wildfires make up only 5.9% of the billion-dollar weather events from 1980 to 2023, they are becoming a more common occurrence.28 The annual burned area in California alone increased fivefold between 1972 and 2018.29

During wildfires, air quality becomes dangerously unhealthy due to a complex mixture of gases and particles from burning vegetation and other materials. Workers who perform jobs outdoors, including emergency response workers, are particularly vulnerable to health hazards.

The health effects of wildfire smoke include eye irritation, sore throat, wheezing, and cough; asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations; bronchitis and pneumonia; adverse birth outcomes; and cardiovascular (heart and blood vessel) outcomes. Between 1992 and 2006, there were 80 fatal occupational injuries due to wildfires.30

A 2019 study of U.S. firefighters concluded that long-term exposure to particulate matter in wildfire smoke greatly increases the risk of dying from lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.31

The Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs receives approximately 2,600 workers’ compensation claims annually from federal firefighters. Of those, about 175 are complex occupational disease claims that include conditions such as cancer, heart disease, and lung disease.32

Because cancer is becoming more common among firefighters, new laws are making it easier to qualify for benefits. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Labor announced a policy that eases the evidentiary requirements needed to support claims for federal firefighters with certain occupational illnesses.33

In addition to smoke inhalation, wildfire-related injuries include burnovers/entrapments, heat-related illnesses and injuries, vehicle-related injuries, and slips/trips/falls. Over a five-year period between 2003 and 2007, a total of 1,301 nonfatal injuries to wildland firefighters were reported, with the most common injury being slips/trips/falls.34

There are also mental health impacts due to wildfires. According to one report, workers’ compensation claims by firefighters in California are more likely to involve PTSD than are claims by the average worker.35

The direct losses of climate change – worker injuries and fatalities, along with health costs – are easily quantifiable, but there are also indirect impacts. These include:

In any of these cases, an injured workers diagnosis, medication, or course of treatment may be delayed, leading to poorer health outcomes. For example, there is a direct association between hurricane disasters and the survival of patients with lung cancer who are undergoing radiation treatment. Researchers followed patients whose radiation therapy was disrupted by a hurricane between 2004 and 2014 and compared them to similar patients who had uninterrupted treatment. Without treatment disruptions, patients survived an average of 31 months after their diagnosis, compared to 29 months when hurricanes interrupted radiation.36

With the staggering impacts of climate change on workers, one would expect laws and regulations to protect them – but this isn’t always the case.

Under OSHA, federal law entitles workers in the United States to a safe workplace free of known health and safety hazards – but the law doesn’t include protections for specific weather events such as extreme heat. Furthermore, not all employers obey the OSHA rules. And state laws don’t necessarily exist, either.

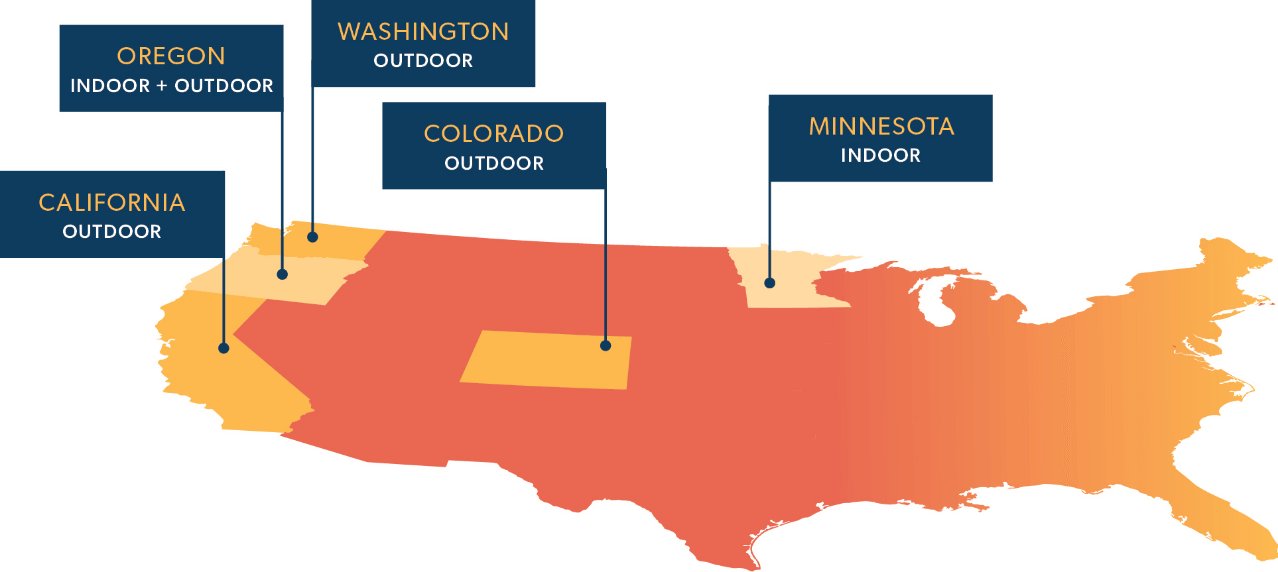

Let’s look at heat protection standards as an example. Currently, there are no federal laws protecting workers from extreme heat. Despite that, only a few states have passed heat protection standards. Approximately 51 million U.S. workers are employed in the six industries with the highest number of heat-related deaths per year – yet only 9 million of those reside in states with permanent workplace heat protection standards.37

California became the first state to pass such a standard in 2006. California’s Heat Illness Prevention Standard requires employers to provide training, water, shade, and planning at outdoor worksites when temperatures reach 80°F or higher. As of this writing, California was also on track to implement a heat protection standard for indoor workplaces.38 Just four other states – Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington39 – have passed standards for heat exposure either outdoors or indoors.

Some states and localities have tried to enact regulations, only to have them defeated. In Virginia in 2021, regulators narrowly voted to reject a standard that would have required employers to provide water and rest breaks at certain temperature thresholds, with mandates for shaded or cooled rest areas.40 A defeat also occurred in Texas in June 2023 when the cities of Austin and Dallas enacted ordinances mandating 10-minute breaks every four hours for construction workers – but the state enacted a law to preempt these and other local ordinances.41

Then, in November 2023, Miami-Dade County in Florida was on track to become the first local government in the country to adopt heat-related protections for outdoor workers – but the county commission deferred the proposed ordinance.42 The new ordinance would have required farms and builders to provide water for workers and 15-minute breaks in shaded areas on extreme-heat days. However, Florida legislators are concerned about the undue burden this could place on employers and are considering legislation that would prohibit local governments from setting worker protection standards.

In recent years as more worker injuries and deaths from extreme heat have occurred, many have advocated for heat safety regulations.

In 2016, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health published criteria for a recommended federal standard for occupational heat stress.43 The nonprofit consumer advocacy group Public Citizen has petitioned for an OSHA heat standard several times, noting that at least 50,000 injuries and illnesses could be avoided in the U.S. each year.44 And in July 2023, Texas Congressman Greg Casar began pushing for the adoption of federal standards to require rest and water breaks for people who work in the heat, as well as training to deal with heat-related illness.45

In October 2021, OSHA took the first step toward a federal heat protection standard when it published an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings in the Federal Register.46 This is an optional step that a federal agency may take prior to publishing a proposed rule. Next, OSHA will develop the rule based on the recommendations from a panel report, public input, and additional research – but it may take years before a final regulation is implemented.

In the meantime, OSHA has initiated a National Emphasis Program on outdoor and indoor heat-related hazards, urging employers to protect their workers,47 as well as a Heat Illness Prevention campaign.48

In the absence of specific regulations, both employers and workers themselves can take steps to reduce the impacts of climate change on workers. The Environmental Protection Agency49 recommends the following: