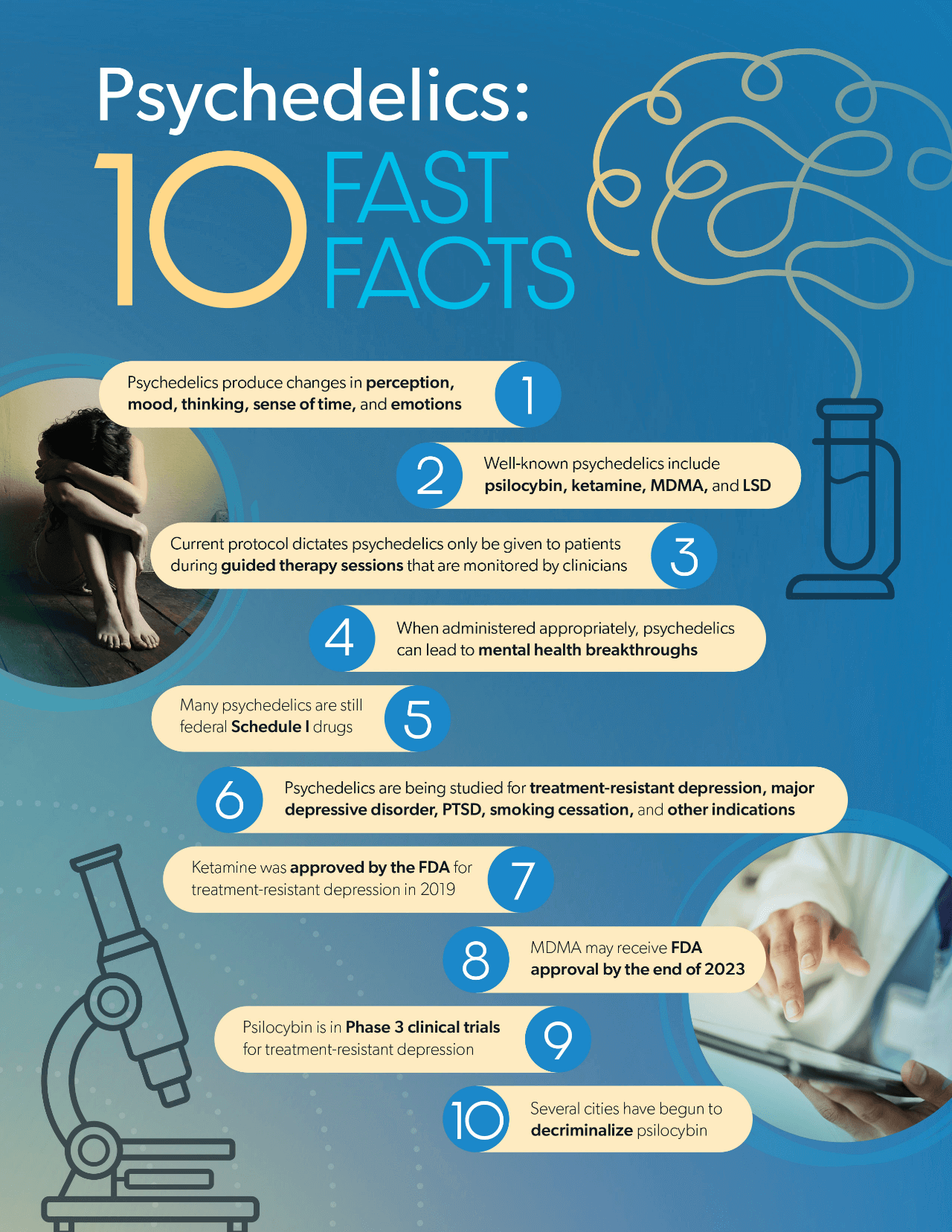

Psychedelics are a class of psychoactive substances that produce changes in perception, mood, and cognitive processes. Psychedelics affect all the senses, altering a person’s thinking, sense of time, and emotions.

Psychedelic drugs include but are not limited to:

Traditionally perceived to be recreational party drugs, the science behind psychedelics’ medical benefits has come quite far in the last decade. According to recent clinical developments, the altered sense of thinking and feeling caused by psychedelics can lead to mental health breakthroughs when appropriately navigated by qualified clinicians.

Certain researchers believe psychedelics have the potential to change the mental health landscape, making it important to understand their relevance to workers’ comp.

By the end of this year a major psychedelic could receive FDA approval for the treatment for PTSD. These developments increase the potential for more drug approvals to come in the next few years. And while there are federal complications as most psychedelics are classified as Schedule I drugs, there is a growing wave of psychedelic decriminalization at a more local level.

At the time of publication of this article, psilocybin alone has been decriminalized in:5

As clinical research continues to evolve, expect to see even more psychedelic initiatives proposed in the coming years.

When used appropriately and under specialized medical supervision, psychedelics have demonstrated significant potential to treat mental illness. But what does this look like?

Though the details vary between different drugs, there is enough common ground in the administration of psychedelic therapy to provide a rough description of therapy.1, 6-7

Psychedelic treatment should only be legally available through certified clinicians in supervised therapeutic settings. Only after patients have received no benefit from first-line, traditional therapies can patients be considered for psychedelic therapy.

When deciding to pursue psychedelic therapy, patients must engage in several standard sessions of traditional therapy with a certified clinician to ensure a trusting therapeutic relationship. Patients are then prepped on what to expect from a psychedelic experience.

Once ready for the experience, a proper medical setting is established, designed to help patients focus internally and dive deeper into the mental processes that are causing them harm. This includes a comfortable room with a bed or couch, two therapists, and possibly a sleep mask and calming music to avoid overstimulation.

The patient is then given the psychedelic medication. Upon administration, the drug floods the brain with hormones and neurotransmitters that evoke feelings of trust and well-being. This promotes a “time-out” from the mind’s ordinary thought process, providing relief from negativity, enhancing a patient’s ability to engage in meaningful psychotherapy.

These intensive sessions last anywhere from three to eight hours, with two therapists guiding the patient carefully into a productive analysis of their mental processes and associations. Depending on the psychedelic, patients may only engage in one psychedelic experience, or possibly a few.

After the psychedelic experience(s), follow-up psychotherapy continues without psychedelics, where the patient processes emotions and insights brought up during the experience.

Ketamine is a powerful anesthetic that has occasionally been used as an analgesic. However, ketamine can also induce dissociation – the feeling of being disconnected from oneself and the surrounding world – and it is this psychedelic property that led the drug to be abused as a party drug known colloquially as “Special K.”

But in the last several years, clinical research has found ketamine’s dissociative properties to have strong antidepressant effects when properly administered. A systematic review of 83 published reports provide support for robust, rapid and transient antidepressant and anti-suicidal effects of ketamine.8

In 2019, the FDA approved intranasal esketamine spray for use in treatment-resistant depression, in conjunction with an oral antidepressant, making ketamine the only psychedelic drug legally available to mental health providers in the U.S. This drug is only available through a restricted distribution system, under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).1

This approval was based on a series of short-term clinical trials and a longer-term maintenance-of-effect trial. In one short-term trial, patients received esketamine or a placebo nasal spray, in conjunction with a new oral antidepressant at the time of randomization. Esketamine demonstrated statistically significant effect compared to placebo on the severity of depression.1

In the longer trial, patients in stable remission from depression who continued treatment with esketamine plus an oral antidepressant experienced a statistically significantly longer time to relapse of depressive symptoms than placebo patients.1

Additional data has also encouraged further research into the efficacy of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for a variety of psychiatric diagnoses including depression, anxiety, and PTSD.9

Like any drug, ketamine comes with precautions, contraindications, and the potential for adverse events. However, considering how new psychedelic therapy is, there is much uncharted territory as to what conditions, comorbidities, patient-specific factors, medications, and other matters may make psychedelic therapy unfeasible.

What is known is that ketamine may lose potency when interacting with benzodiazepines, a drug class commonly found in workers’ comp. Additionally, common side effects seen in ketamine assisted therapy include nausea, vomiting, and agitation.

However, it is crucial to remember that psychedelic therapy must be properly administered, wherein lies a new concern. Like all FDA-approved medications, ketamine can be prescribed off-label for other indications that providers deem appropriate. This has led to the proliferation of ketamine clinics across the country. Enough have popped up that the Department of Veteran Affairs now covers treatment in certain ketamine clinics.10

From 2015-2018, the number of ketamine clinics in the country rose from 60 to 300, but since the 2019 approval, there are estimated to be hundreds to thousands of clinics specializing in ketamine therapy.11

According to the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) – the research institution that has led the way on psychedelic research– a majority of ketamine clinics do not provide adjunct psychotherapy with ketamine treatment. It has also been reported that certain ketamine clinics engage in aggressive marketing and offer deliveries of ketamine – a noteworthy concern as psychedelics should be administered in medically supervised settings.10

As the utilization of ketamine therapy evolves, the need to ensure proper oversight may grow.

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) – known by the street names ecstasy and molly – is both a stimulant and psychedelic that produces an energizing effect that distorts time and perception and causes intense euphoria.

While illegal recreational use has been popular for decades due to MDMA’s euphoric effects, those very same effects have proven to have therapeutic value when administered in an appropriate clinical context, particularly for the treatment of PTSD.

In 2017, the FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of PTSD in response to positive results from Phase 2 clinical trials, agreeing that this treatment may have a meaningful advantage over available medications for PTSD.12

In one Phase 2 trial, 56% of patients treated with MDMA no longer qualified as having PTSD at the two-month mark; that percentage grew to 68% within 12 months.12

An analysis of six double-blind controlled clinical trials found MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to be efficacious and well-tolerated in a large sample of adults with PTSD.13 An additional Phase 2, double-blind, dose-response trial found MDMA-assisted therapy to be effective and well-tolerated in reducing PTSD symptoms in veterans and first responders.14

Due to the nature of their work, first responders such as firefighters and police officers are regularly exposed to potentially traumatic events, such as witnessing horrific injuries and deaths, making them far more likely than the average person to develop PTSD.

Presumptions for PTSD without an accompanying physical injury have sprouted across the nation, meaning workers’ comp coverage for PTSD treatment is now relatively common. Should MDMA receive FDA approval as game-changing treatment for PTSD, this unique patient population could see significant utilization.

At this time, two Phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have been completed and are serving as the basis for a new drug application (NDA) that is expected to be submitted to the FDA at some point in Q3 of 2023.2

In both Phase 3 trials, patients who received MDMA-assisted therapy saw significant positive changes from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5, as well as reduced disability scores, and a lack of adverse effects.2,15

While MDMA may require some back and forth between researchers and the FDA for additional data, as is often the case with NDAs, it is highly likely that MDMA will very soon be approved, considering the significant cooperation the FDA has had with researchers.

In fact, the FDA allowed select patients early access to MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD in 2020, recognizing it a potentially beneficial investigational therapy for people facing a serious or life-threatening PTSD, for who current options have not worked, and who were unable to participate in Phase 3 clinical trials.16

In addition to ongoing research for the treatment of PTSD, MDMA will soon begin Phase 2 clinical trials for the treatment of schizophrenia.17

These trials will specifically seek to treat the asociality – impaired social motivation – symptom of schizophrenia, in the hopes of causing significant functional improvement. Though many antipsychotic medications can treat schizophrenia, deficits exist in the treatment of asociality.

While there was little-to-no report of adverse events, MDMA does come with side effects like any other drug. MDMA transiently increases heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature in a dose-dependent manner. However, serious adverse events involving administration of MDMA in clinical trials have been uncommon and non-life threatening.12

But outside of a controlled environment, MDMA is followed by a period of neurochemical recovery, when low serotonin levels are often accompanied by lethargy and depression. Regular usage can also lead to serotonergic neurotoxicity, memory problems, sleep disturbances, lack of appetite, concentration difficulties, depression, heart disease, and impulsivity.

Additionally, outside of a clinical environment, MDMA has been linked with increased mortality when mixed with benzodiazepines, anesthetics, amphetamines and stimulants, ethanol, opioids, certain antidepressants, and other drugs.18

The active ingredient found in hallucinogenic “magic mushrooms,” psilocybin is a naturally occurring psychoactive substance with mind-altering effects that include changes in perception, a distorted sense of time, perceived spiritual experiences, hallucinations, and euphoria.

While historical evidence has found that psilocybin has been used for at least 6,000 years,19 modern research has found psilocybin to have potential mental health applications when administered in an appropriate clinical setting.

In 2018, the FDA granted psilocybin-assisted therapy Breakthrough Designation for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), later granting the same designation for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in 2019, noting that psilocybin-assisted therapy may have a meaningful advantage over available medications for these indications.20-21

A Phase 2 double-blind clinical trial found that psilocybin reduced depression scores significantly in patients with TRD, with 29.1% of psilocybin participants in remission after three weeks – a higher response rate seen across equivalent lines of treatment for TRD.22

Positive results such as this have led to the launch of Phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials for psilocybin-assisted therapy for the treatment of TRD.3

If psilocybin therapy continues to demonstrate significant improvements in mental health, it is possible psilocybin could see a new drug approval within a few years.

Studies so far have also shown promise for MDD. A Phase 2 randomized clinical trial found that psilocybin-assisted therapy was efficacious in producing large, rapid, and sustained antidepressant effects in patients with MDD, with a follow-up studying noting that such effects may be durable for at least 12 months in certain patients.23-24

In addition to TRD and MDD, more studies are underway to test pisolcybin’s impact on other indications, such as:25-27

An open-label pilot study saw 12 out of 15 participants (smokers averaging 31 years of use) exhibit seven-day point prevalence abstinence at 6-month follow-up after undergoing psilocybin therapy. This exceeds smoking cessation rates commonly reported for other behavioral and/or pharmacological therapies (typically <35%).25

Current research has proven so promising that Johns Hopkins University received a $4 million federal grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH) to continue researching psilocybin’s potential to assist in smoking cessation.4

Like any drug, psilocybin comes with side effects and the possibility of adverse events. Common side effects include confusion, fear, hallucinations, headache, dizziness, fatigue, high blood pressure, nausea, and paranoia.

And with the potential for side effects such as this, comorbidities and drug-drug interactions must be considered to avoid any potential harm to patients. However, when administered in clinically appropriate settings, the potential for adverse events can be mitigated.

An evaluation by Neuropharmacology found that the abuse potential and potential harms of medical psilocybin to be low when administered according to a medical model that addresses these concerns.26 Additionally, human studies have indicated no physical dependence potential.26

In fact, Johns Hopkins University researchers recommend psilocybin be rescheduled from Schedule I to Schedule IV, once the drug clears Phase 3 clinical trials.27

If psychedelics research evolves to the point of drug approvals, these medications will work their way into mainstream healthcare, and workers’ comp could see some of that activity due to its applications in behavioral health, and especially within populations that qualify for mental health presumptions.

Avoiding drug-drug and drug-disease interactions are just the start. As more research unveils the ins and outs of psychedelic therapy, the workers’ comp industry must work to keep pace with these new drug trends. Understanding how these drugs could impact an injured worker’s overall health, their injury, and the other components of their care will be important.