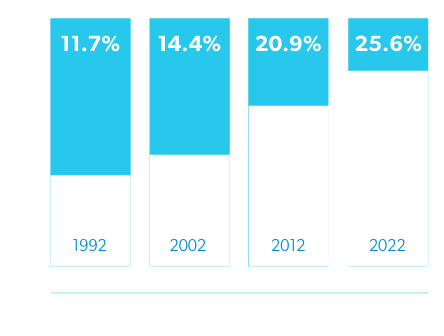

The aging of the American workforce has been a subject of much discussion in workers’ compensation, and for good reason. By 2020, one out of four workers is expected to be 55 or older.1 This startling fact raises concerns about injury rates and health issues that become more likely with age, such as comorbidities, polypharmacy, and longer recovery times.

These are legitimate concerns that deserve the attention they are receiving. But injured workers are not the only people who are aging. The American population is getting older, including the people we count on for care – physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals.

Over 50% of U.S. physicians are over the age of 50 and one third will be over the age of 65 in the next decade.2 Experience is a valuable asset in medicine, but this is not just an issue of more mature providers. Thirty percent of physicians retire between the ages of 60 and 65,2 and more are leaving the profession before retirement age due to job dissatisfaction and burnout. A limited number of residency programs, combined with fewer young people aspiring to careers in medicine, has restricted the number of new physicians. All of which means that physicians are leaving the profession faster than they can be replaced.

The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortage of 47,000 – 122,000 physicians by 2032,2 with family and internal medicine, emergency medicine, hospitalists, and radiologists all falling within the top 10 specialties experiencing shortages. Urgent care, cardiology, orthopedic surgery, neurology, general surgery, and anesthesiology are all included within the top 20.

By 2030, the share of the population aged 65 and older will increase from 13-19%.3 Because older adults consume a disproportionate share of healthcare services, the supply of physicians is shrinking just as the demand for care is expanding.

And we cannot count on allied health professionals to fill the gap. The average nurse age is now 514 and 44% of physician assistants are over the age of 40.5 According to the Center for Health Workforce Studies, approximately 15,400 new nurse practitioners and physician assistants will be needed each year between 2016 and 2026 to fill new positions and those being vacated.6

Ironically, the size of the healthcare workforce overall is expanding and now accounts for 14% of the total U.S. workforce. But the increased staffing is occurring in administrative positions, not frontline care providers,7 which adds cost without increasing access to medical care.

Older injured workers often require more complex courses of treatment, which alone raises the specter of higher medical costs and increased compensable time. In addition, the longer wait times and higher professional fees for healthcare providers could lead to compromised care for patients.

The risks of higher costs and suboptimal care exists for all healthcare, of course, but the threat is greater to workers’ compensation programs for the following reasons:

Some efforts are being made to address physician shortages and modify workers’ compensation laws to keep up with the changing healthcare landscape. For example, California recently spent nearly $70 million to pay off student loans for doctors with at least 40% MediCal patients. And a new bill was introduced in the New York State Senate to examine how connected health technology could improve outcomes for injured workers and increase access to care providers.

Any positive measures to address physician shortages and/or mitigate its consequences for workers’ comp are welcome, and we need more of them. Unfortunately, even if all 50 states took aggressive action, the remedies could not be realized quickly enough to forestall the impending issues. Already the wait time for new-patient appointments has increased by 30% or more in 15 major metropolitan areas since 2014,8 and the number of qualified medical evaluators in California declined 20% from 2012 to 2017.9

The double threat of an aging workforce combined with a shortage of healthcare providers is upon us, and workers’ compensation payers should take proactive steps to meet the challenge, including:

The aging worker population and healthcare provider shortage are matters out of direct control, but workers’ compensation payers, managed care organizations, and their partners can work together to test and implement new strategies that will continue to contain costs and ensure the best possible outcomes for injured workers.