The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world forever. Nearly every task imaginable has required safety reconsiderations – grocery shopping, exercising, visiting friends and family, traveling, and of course, working.

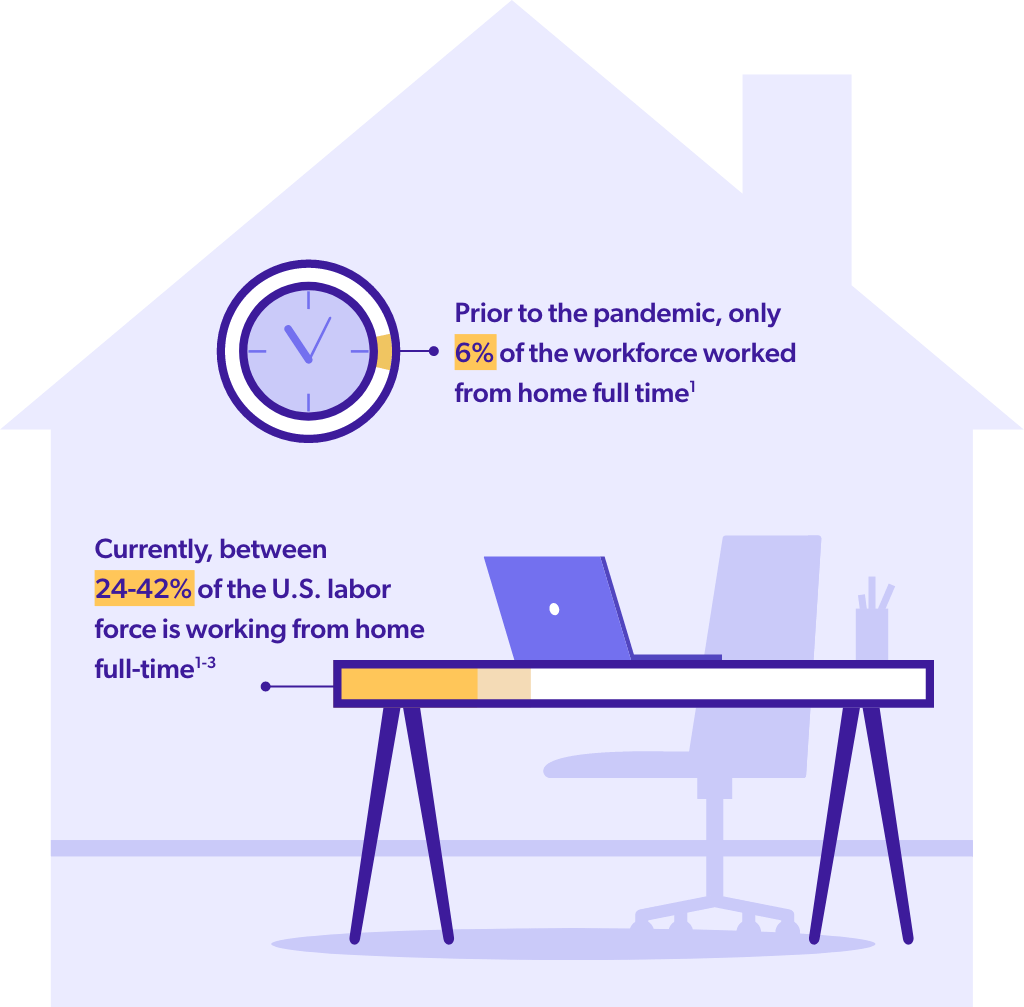

Many employers have adjusted to the pandemic by allowing their workforce to work from home (WFH) to mitigate viral transmission and protect employees. However, extensive isolation and other factors, some general and some unique to WFH employees, have created cause for concern surrounding mental health.

There are a wide range of stressors stemming from this pandemic that impact virtually everyone. In addition to direct fears surrounding the coronavirus, people across the nation must deal with extensive social isolation and disruption to family and support systems – including the loss of loved ones, as well as financial and long-term economic worries, and general uncertainty.

However, specific to WFH populations, employees may face other unique stressors. Many employees with children face additional caretaking responsibilities, with 50% of parents agreeing that it is difficult to work from home without interruption.4 Furthermore, suboptimal workplaces can lead to decreased mental wellbeing,5 and an estimated 78% of WFH workers don’t have a dedicated workspace.6

Most notably, workers face difficulty differentiating their work life from their home life when working from home.

These workers spend an extra 32-49 minutes working per day7-8

69% experience burnout symptoms9

59% take less paid time off (PTO)9

37% feel isolated and concerned about their performance10

36% said their stress levels increased10

Meetings are up 13%8

Among some individuals, greater stress can mean greater mental health impact. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 41% of U.S. adults are struggling with their mental health or substance use during this pandemic.11

Poor mental health negatively impacts job performance, productivity, and physical capability and daily functioning, and employees at high risk of depression can have higher healthcare costs, in some cases even more so than employees who smoke or are obese.12

With mental health symptoms on the rise, people are coping in various ways, with noted increases in the utilization of psychiatric drugs and substance use.

Antidepressants utilization increased 9.2%13

Antianxiety drug utilization increased 10.2%13

Anxiety medication prescriptions increased by 2 million in 202014

Positive results in workplace drug tests are at a 16-year high15

29% of people increased alcohol use during the pandemic16

12% of adults started or increased substance use11

Adults with symptoms of anxiety and depression were 2x likely to increase drinking16

People with depression were 64% likely to increase alcohol intake16

People with anxiety were 41% likely to increase alcohol intake16

The risk? Psychiatric drugs such as antidepressants and benzodiazepines can produce dangerous or even potentially fatal side effects when mixed with alcohol or other substances. And drug-alcohol interactions don’t end there.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) lists a number of commonly used medications, both prescription and over-the-counter, that can have harmful interactions with alcohol. Medications listed on the NIAAA site include, but are not limited to conditions such as:17

The negative side effects can range from headaches, drowsiness, and reduced coordination, to potentially life-threatening effects that include heart problems and respiratory distress – all of which are detrimental to employees’ performance, and most importantly, their health and safety.

While WFH employees are all susceptible to mental health concerns due to extended isolation, women may face higher risks than men.

In general, women are more likely to report mental health concerns than men – women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression.18 They are also more likely to receive psychiatric medications – benzodiazepine use is twice as prevalent in women than in men.19

But women might also face additional stressors when working from home.

Women spend 40% more time on childcare than men,20 and women are typically burdened more with taking care of children at home. Half of parents with children said it is difficult to get work done without interruption,4 while 4 in 10 working mothers say it is harder to balance work life and family responsibilities.4

There are many ways employers can address the growing mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This can include workplace practices as well as access to wellness initiatives.

First and foremost, employers can help to eliminate the stigma surrounding mental health by encouraging employees to practice self-care and explore mental health resources available in their benefit plans.

This can include general discussions about mental health, as well as small pragmatic gestures such as:

For prevention, wellness programs may be utilized to encourage proper diet, exercise, and stress management. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle and developing proper coping techniques can help individuals to endure stress. Furthermore, offering employees tools like mindfulness apps or meditation programs can be used to reduce stress.